.jpg)

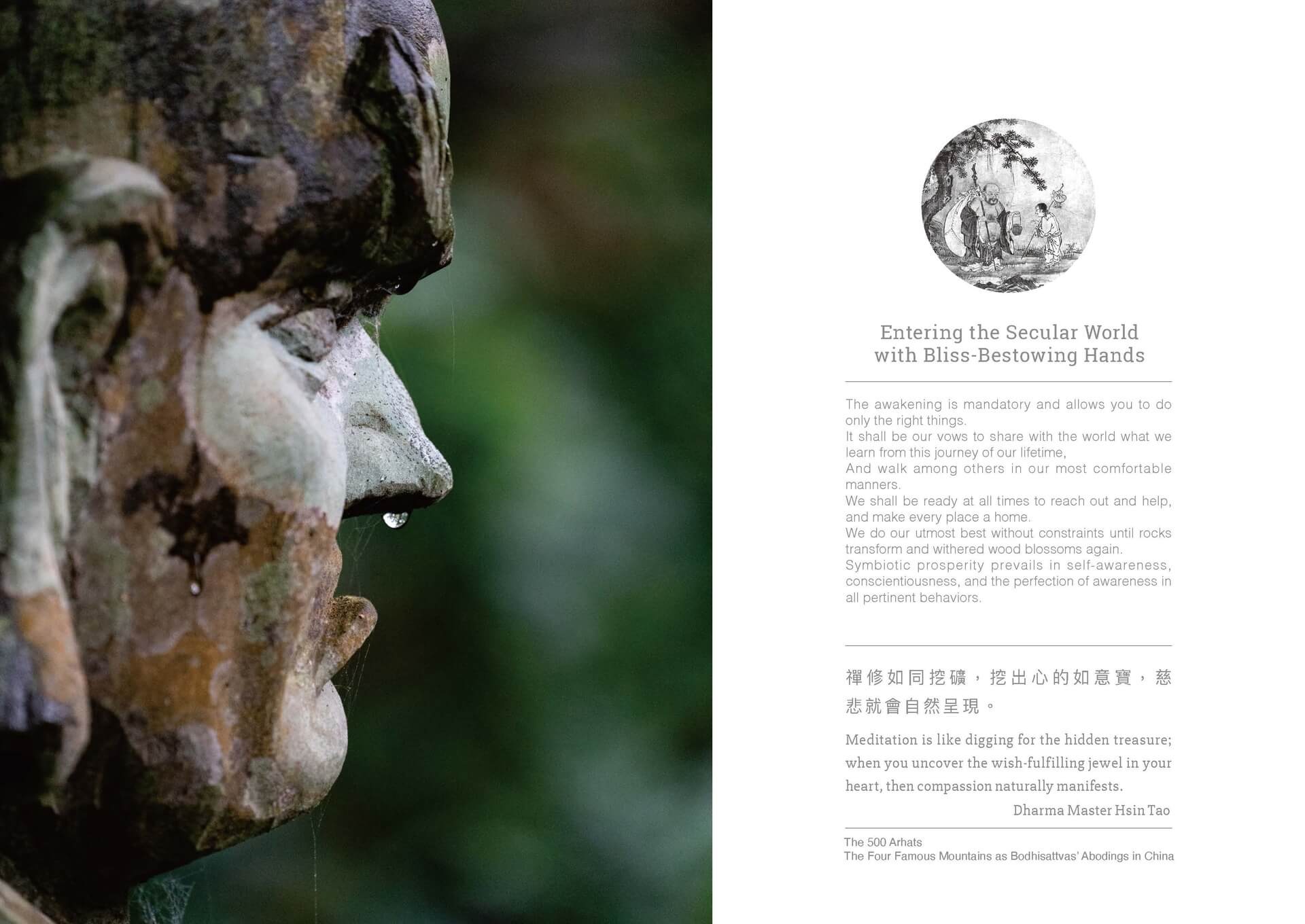

【Entering the Secular World with Bliss-Bestowing Hands】

Entering the mansion bare-chested and -footed and with a smile ear-to-ear about the mud-smeared face and dust-strewn hair;

Without a deity's true secret of supernatural power, (he the One) simply demands deadwood to blossom.

With the awakening of consciousness towards enlightenment in place, one no longer bothers with one's poor look without a shirt or shoes on. And with no pretense, one's behavior always naturally reflects the compassionate joy of letting go of attachments. The mansion in the verse refers to the present abode and is a metaphor for our scorching homes in all three realms of Trailokya. Thus accordingly, the first verse describes how a practitioner is free of all constraints and treats troubles as Bohdi and life and death as Nirvana. He nonetheless does not stay put in the comfort zone of Nirvana but views people's scorching houses as an address of joy, where he can conduct Buddha's teachings in line with a monastic's six precepts to benefit all sentient beings.

Verse 2 describes how one laughs off his poor appearance to suggest that the practitioner has already attained a lasting state of mind of tranquility that fuses seamlessly with the hustles and bustles of our secular world. The practitioner can thus bear the unbearable and remains untethered in adversities. Armed with such mental capacities, the practitioner has at his disposal endless means to convert sentient beings from bitterness to bliss and elevate them from worrisome entanglement."If looking beat in appearance is the price to pay for such meaningful work, so be it." The legendary figure of Monk Bu-Dai (Big-bellied Monk with the cloth bag) of the Ming Dynasty is perhaps a fit manifestation of the monologue quoted above of the practitioner. The monk was homely dressed and carried his cloth bag wherever he went trotting the secular world to collect and remove people's troubles into the bag, and always wearing a contagious smile no matter how demanding it was to remove all the worldly troubles.

Phrases 3 and 4 of the second verse refer to the true state of the conscious mind per se that is pure and never second-guesses, while compassion, meditation-induced composure, and wisdom belong as its innate capacities. Once consciousness transforms to enlightenment, the practitioner no longer needs to seek secrets of the Truth as enlightenment is divinity itself and embodies the Truth. Once consciousness becomes enlightenment, the practitioner can help liberate sentient beings in endless and wonderful ways thus enabled, so that people can follow in his footsteps towards enlightenment. ‘Deadwood blossoming’ describes how people miraculously comprehend their original selves, i.e. their own nature-born minds. When their original selves/minds stay unreachable, people are comparable to deadwood, but an enlightened practitioner would rejuvenate such deadwood back to blossoming with Dharma nutrients of Buddha's teachings. Such is a state described in Chan/Zen Buddhism as ‘An enlightened mind sees through to the original nature of oneself, and seeing the original self means to reach Buddhahood.

Entering the Secular World with Bliss-Bestowing Hands

Entering the Secular World with Bliss-Bestowing Hands is the title of the present chapter, and it marks the last painting in the Ten Oxherding series. Depicted is a monk covered in dust and dirt all over, yet he is full of smiles. The monk is among ordinary people and leads a seemingly common life like everyone else. In fact, however, the monk is the enlightened one and a saint, who appears to be an average person - but one devoid of constraints and unrestrained by formalities. Coming to mind is the stone sculpture with the theme of the 500 Arhats that is well tucked away in one of the four famous mountains of the Ling Jiou Mountain Monastery in Taiwan. The sculpture shows the Arhats in many different postures and facial expressions that animate life, yet they convey the message that they care about people's worldly sentiment.

The previously discussed ‘Returning To The Original Self’deals with the self-elevating appreciation of Dharma, and the progressive final chapter relates to a higher degree of achievement, in that the Dharma benefit outgrows the self to benefit others as well. Such are the varying objectives pursued respectively in Theraveda and Mahayana, with the latter placing an unchallenged focus on altruism for mankind to pursue a livelihood that is freer, purer, and more creative. Such mentality is similar to that of our LJM Patriarch's and is evidenced in Dharma Master Hsin Tao's journey of how one lone ascetic monastic created a monastery from scratch, yet never flinched in the face of hardship when laboring to benefit all sentient beings. In the span of a year, we made use of the Ten Oxherding painting series to illustrate the ten unskippable stages of Dharma study and practice. For each stage, we availed ourselves of a matching boulder stone either of natural formation or coming with smart craftsmanship of sculpture. The ten boulder stones or stone sculptures are invariably located throughout the LJM monastery as visitor attractions. In closing, we herewith reach out to your attention to our sincere invitation to (re-)visit our monastery and track down the ten boulder stones for a soul-searching visit with an exercise of the mind to recall teachings we shared through the Tex Oxherding. We look forward to the day when you turn around to tell stories of your encounter with fables associated with the ten boulder stones up in LJM hilltops.

In the span of a year, we made use of the Ten Oxherding painting series to illustrate the ten unskippable stages of Dharma study and practice. For each stage, we availed ourselves of a matching boulder stone either of natural formation or coming with smart craftsmanship of sculpture. The ten boulder stones or stone sculptures are invariably located throughout the LJM monastery as visitor attractions. In closing, we herewith reach out to your attention to our sincere invitation to (re-)visit our monastery and track down the ten boulder stones for a soul-searching visit with an exercise of the mind to recall teachings we shared through the Tex Oxherding. We look forward to the day when you turn around to tell stories of your encounter with fables associated with the ten boulder stones up in LJM hilltops.

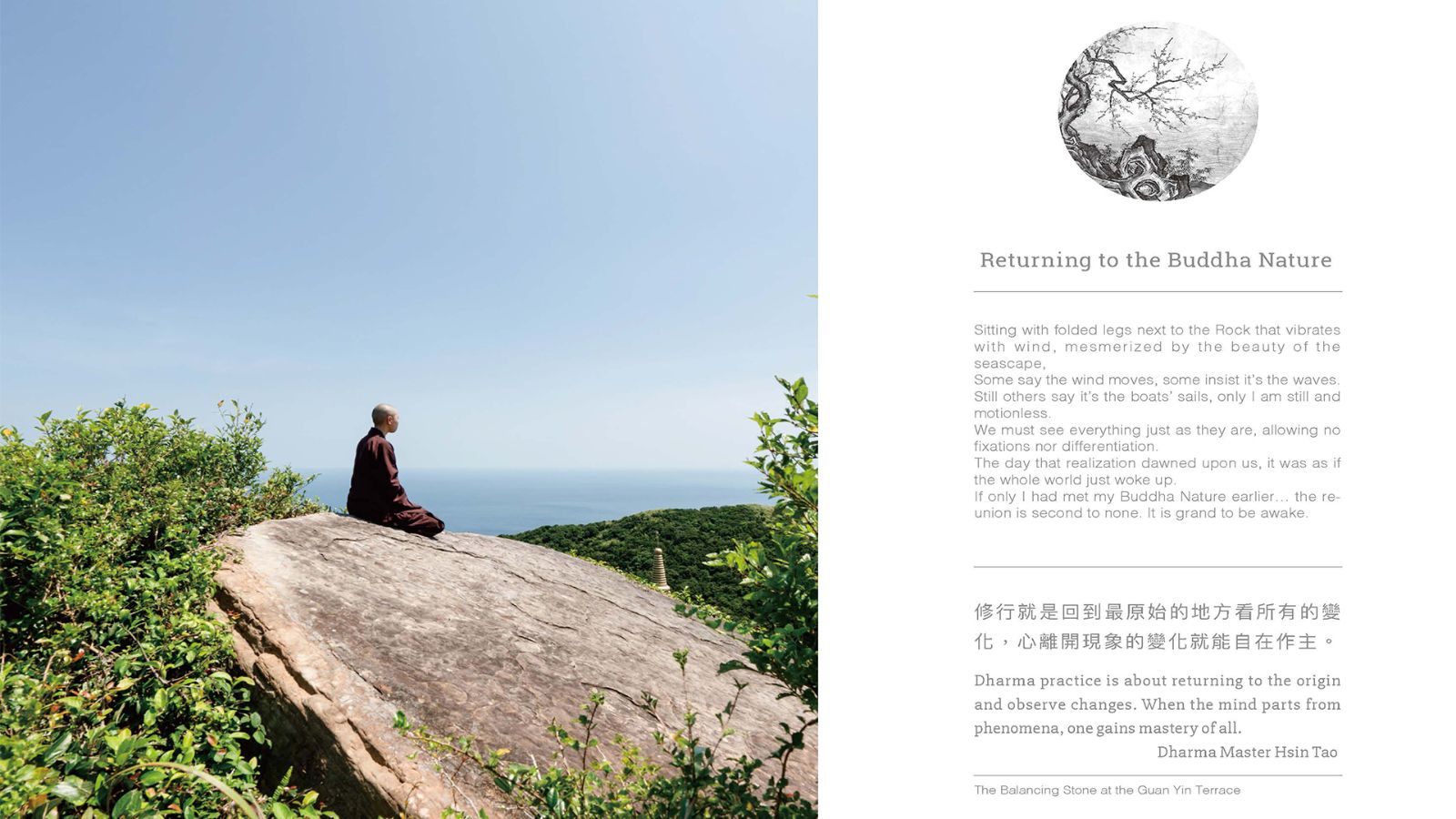

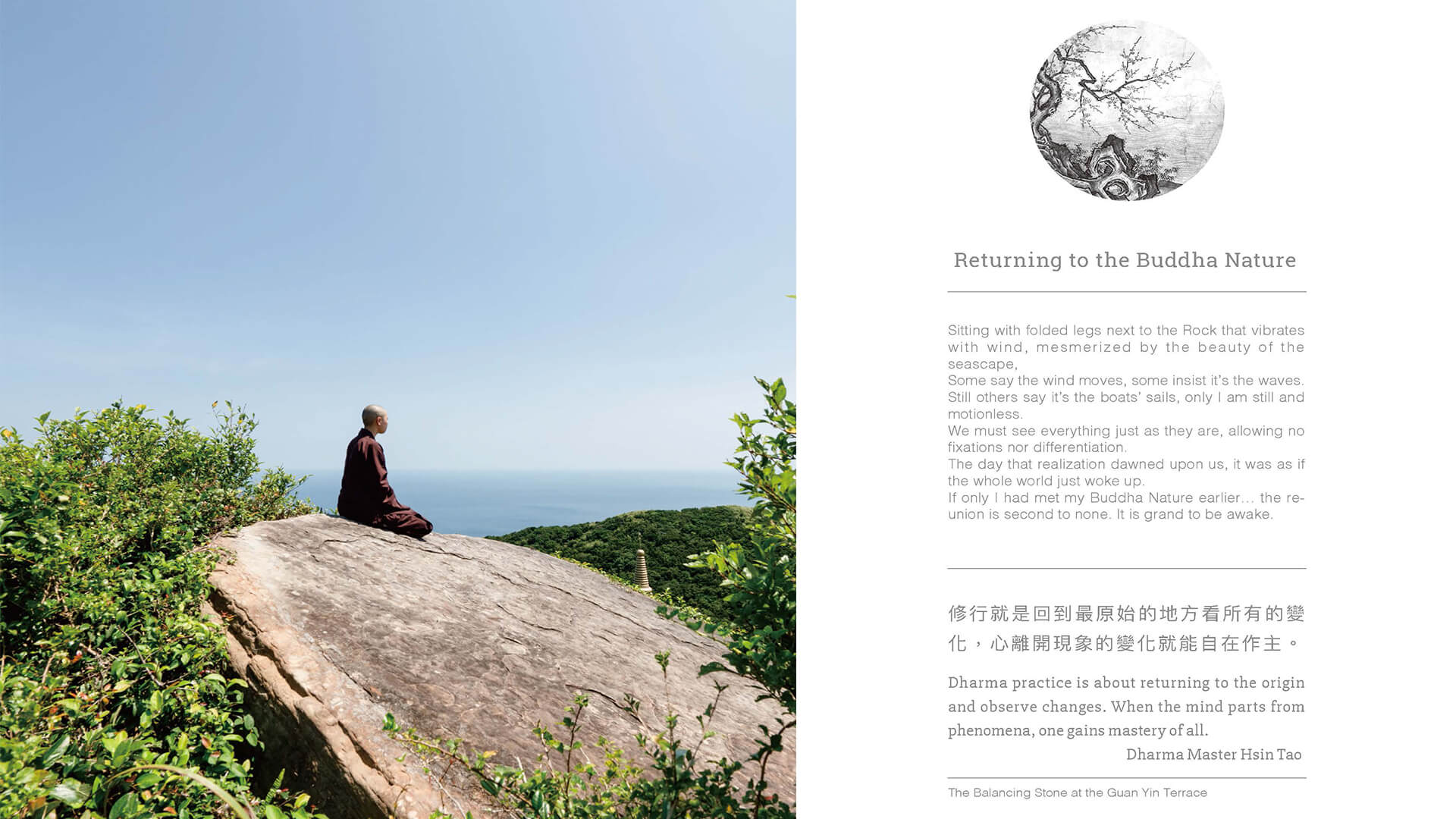

Returning to the Buddha Nature

【Returning to the Buddha Nature】

Having regained my very own Buddha nature, all the efforts made seem to become in vain. It would have been better to be blind, deaf, and dumb.

From inside I can not see the front yard of the abode, but the river still flows and red flowers bloom just as they are.

'Having regained my very own Buddha nature, all the efforts made seem to become in vain' refers to the realization journey which began with searching for the ox. All possible efforts were exhausted and hard work accomplished to retrieve the Buddha nature, and one then realized that the journey itself was not called for, since all has been innate all along and there is no arising nor ceasing and nothing actually comes and goes. So does our Dharma practice.

'It would have been better to be blind, deaf, and dumb’ refers to the context that at the moment it would be a wasteful undertaking to debate on the issue of ‘returning to the Buddha nature', instead, a momentary switch to meditation might be what’s called for. The mind of awareness watches without seeing and listens without hearing, like the blind and the deaf, shutting out the outside world with all the changing panorama. The Buddha nature is thus the mind’s abode, where its stability remains in the state of the ultimate realm.

The verse 'From inside I can not see the front yard of the abode,but the river still flows and red flowers bloom just as they are.’Staying inside in the cottage, whatever is in front or at the back of it exists neutrally and neither active rejection nor passive inclusion would be necessary. All fleeing phenomena impose no lingering obstacles to the mind implies that the enlightened mind has surpassed the state of relativity to arrive at that of absolute. Should there be an object to see, a relativity between the person to see (subject) and the thing to be seen (object) would exist. The mind of ultimate awareness, however, demonstrates naturally just like the way the river flows and flowers bloom. The entire universe is ‘true emptiness', 'wonderful existence’, and ‘reality' as well. The mind contains all time and space, and once our practice reaches such a milieu, our mind will be like the blue sky above and the occasional passing clouds (of worries and wanton ideas) go by without leaving traces behind. Such is a more advanced state of mind achieved by deep meditation.

Returning to the Buddha Nature

The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch records a story of two monks arguing heatedly about a flapping flag in a gusty wind. One claims that it is the wind that moves, and the other insists that it is rather the flag. The sixth Chan Patriarch Hui Neng noted that their faces already turned beat-red and yet neither would back down. He then said to them,'It is neither the wind that is moving nor the flag that is moving. It is your mind that is moving'. Our mind actually pertains to nothing physical, but people mistake the opposite for a constant. Behold, alas, that the mind is the trickiest for targeted treatment. All external phenomena are the result of our mind reflection like the wind and the flag in the above story and as such, they are beyond our control. As long as we remain aware of our mind, we know how to deal with external distractions without moving even the small finger. Whichever it is that the move comes from the wind, the flag, or the mind, it boils down to a change of thought. When the mind remains unfathomed, our subjective sovereignty stays firm and remains unaffected by external adversities.

Our mind actually pertains to nothing physical, but people mistake the opposite for a constant. Behold, alas, that the mind is the trickiest for targeted treatment. All external phenomena are the result of our mind reflection like the wind and the flag in the above story and as such, they are beyond our control. As long as we remain aware of our mind, we know how to deal with external distractions without moving even the small finger. Whichever it is that the move comes from the wind, the flag, or the mind, it boils down to a change of thought. When the mind remains unfathomed, our subjective sovereignty stays firm and remains unaffected by external adversities.

Those who possess an excellent command of Dharma appear rather similar to those knowing neither Buddha nor Dharma, as the nature in both cases is innately clean and uncontaminated. Nonetheless, those who practice Chan Buddhism do differ from ordinary people sans enlightenment. The former resides in the ups and downs of the secular world amidst all passing phenomena but manages to alleviate themselves above it all, observing and registering without engagement or attachment. They thus rise above the mundane to achieve by letting Nature take its course. Coming to mind is the comparable history of how the Ling Jiou Mountain Buddhist Society (LJM) arrived at where it stands today, from Dharma Master's decade-long solitary retreat for practice in run-down cemeteries, over another two-year solitary retreat with fasting and a Bodhisattva coming out from a stone cave to embark on a journey of his calling to receive formal recognition with the highest possible honor from all three major Buddhist traditions Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana to form the bedrock for a foundation that led to the ultimate establishment of the LJM as we know it today.

Dharma practitioners tend to perceive real-life happenings from the viewpoint of ultimate truth, i.e. to base everything on their inherent nature without a shred of any weary concern and by restoring everything back to its origin. They do that by forgetting any egocentrism to let the world run its natural course without imposing any man-made borderline and connections. Just like the 'Returning to the Buddha Nature' of the Ten Oxherding painting series - as long as we manage to stay focused on the awareness of the mind and employ that for reflections in daily life, our intellectual capacity will always shine through without deterring the mind. Put differently, we then perceive everything in clarity without getting bothered by their presence.

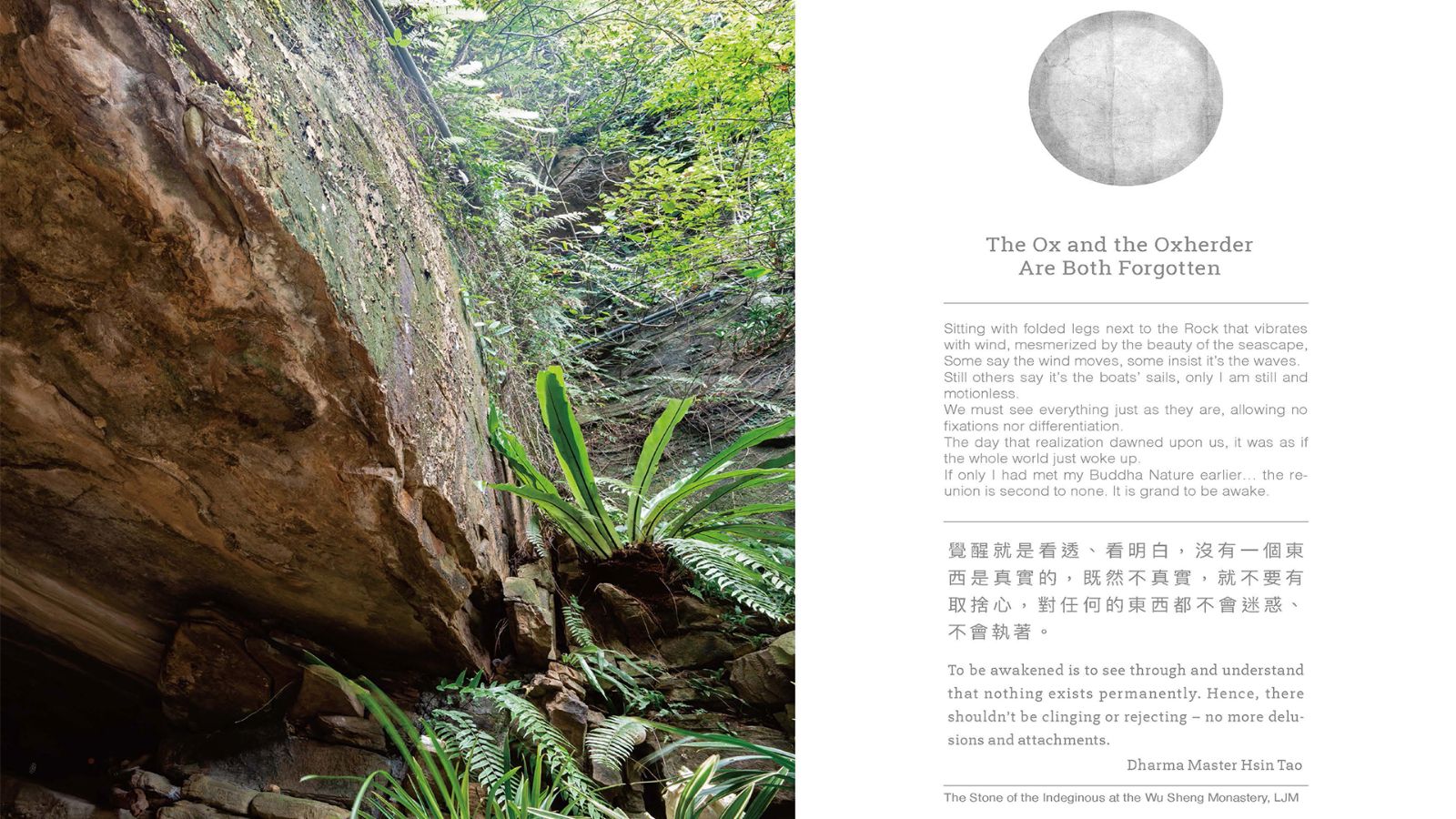

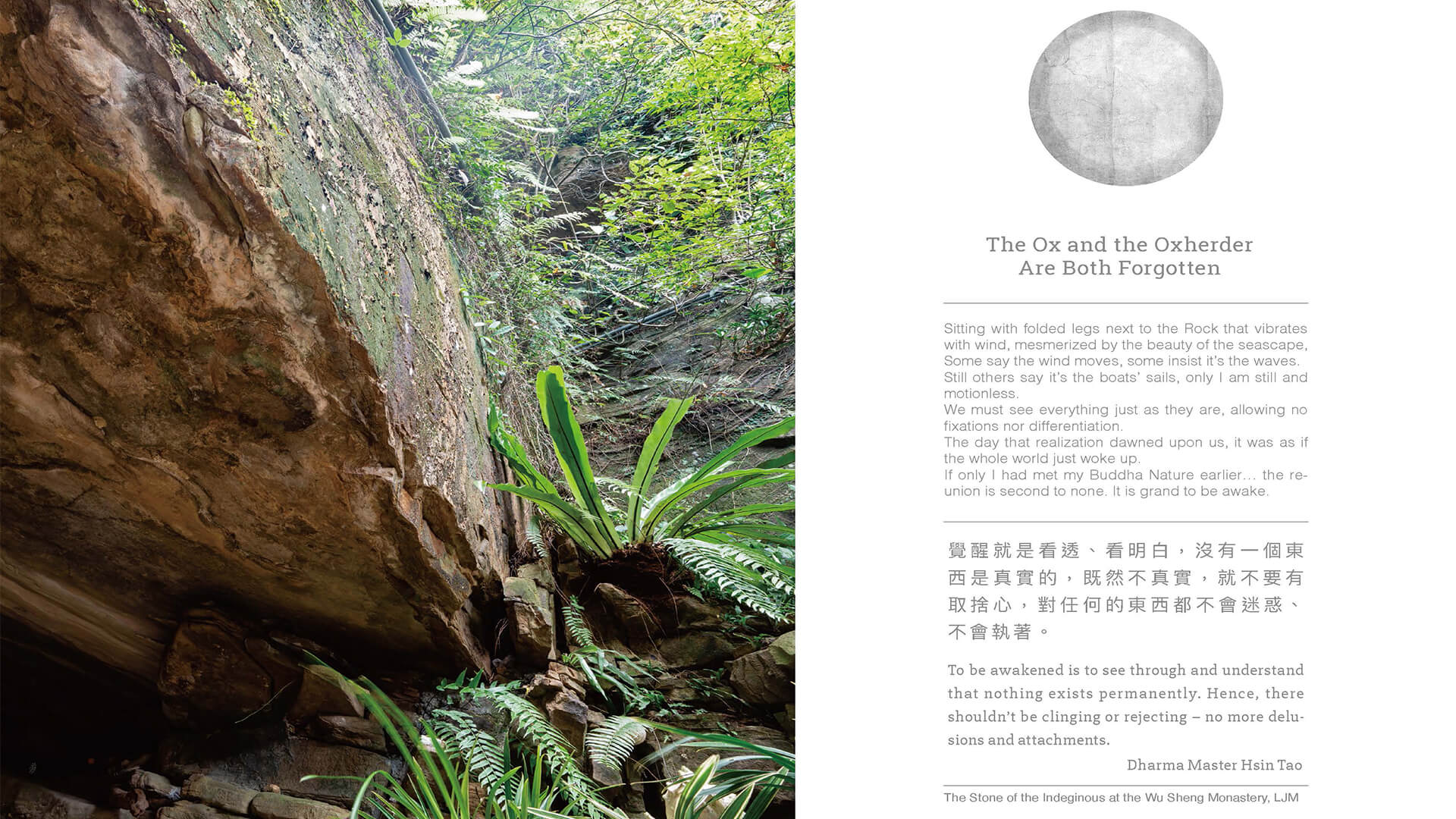

The Ox and the Oxherder are both forgotten

【The Ox and the Oxherder are both forgotten】

The whip, the rein rope, the oxherder, and the ox are all of the void, Hard for messages to cross the vast body of bluish-green skies;

Vying to melt snowflakes over the flames of a red-hot stove, Only until this stage it becomes compliant with ancestral expectations.

We began with the search for the ox before going through the stages of finding the ox's tracks, seeing it, taming it, herding it, riding it home to the stage of forgetting the ox with only the herder left behind. We now advance to the next stage where both the ox and the herder are forgotten. The immediate stage before, i.e. forgetting the ox with only the herder left behind, is already one such scenario where there is no ox to herd,nor any to be tamed and kept, and one could but to let go of even the notion of wisdom - the Bodhicitta. The present stage of ‘both the ox and the oxherder are forgotten’goes further to illustrate that the Bodhicitta itself refers back to the origin of the void and the emptiness. The ox is out of reach, as is the oxherder. Both the heart and its abode are empty as conveyed by the phrase ‘both the ox and the oxherder are forgotten’to arrive at an absolute stage (of the void) as described in the opening verse of the poem at the top of the essay.

Casting the whip, the rope, the herder, and the ox all aside without a shred of concern any longer; messages cannot cross the vast skies, but everything is in plain sight. It follows naturally that no snowflakes stay without melting over burning flames. Once the stage as such is reached, there is no longer any attachment to the dichotomy of beauty and ugliness, good and bad, right and wrong, life and death, etc., to a stage that is truly real. When the Buddhist studies reach the stage where one stays free of any secular emotions and is capable of overseeing any sentimental responses, one on longer make comparisons and distinctions - put differently, forgetting both the herder and the ox suggests that the notions of both the living and the Buddha become void and one sits squarely in the seat of the Dharma nature. A comparable scene would be that one has reached the side yonder but still carries the canoe that is no longer worthy of any attachment - a conscious let-go is the simple solution. A real manifestation of the original nature of void only then appears when one rids him/herself of wanton desires along with the disappearance of a discerning and enlightened heart/mind.

'The vast bluish-green sky’actually describes the unlimited, borderless domain of the heart/mind that registers no beginning or end. The scenario where ‘messages cannot cross the vast body of the bluish-green skies’refers to a stage where no verbal descriptions suffice and all cognitive notions find themselves in shambles and inertia. Messages do not get across, because there is no use for any mental exercises, nor can any mental exercises can apply to express or explain the status quo. The scenario and the condition, consequently, is referred to as ‘the Unimaginable’.

The verse ‘Vying to melt snowflakes over the flames of a burning stove’describes the status of the heart/mind of this stage when no differences are made between beauty and ugliness or good and bad to arrive at the comprehension of ‘one for all and all for one’- just like flames over a burning stove do not tolerate any falling snowflakes, In such a dire absolute, there is nothing to be gained for keeps as put succinctly by the following verse from the Heart Sutra - ‘and no ignorance or ending of ignorance. up to and including no old age and death or ending of old age and death.’

‘In sync with the ancestors’means in line with ancestral expectations which can be taken further to suggest ‘ matching the mental code passed down from Buddhas of all ten Dharma realms’. When Buddhist practice reaches this stage, words or phrases no longer apply, no capabilities nor any lasting stamina are necessary, to fit the heart/mind into the void and emptiness that equals the absolute scenario where both the person nor the Dharma are non-existing, because the code of heart/mind of Buddhas is matched in that very moment. All 84-thousand Dharma approaches must eventually repatriate to the state of absolute paramita, away from any contrast or comparison, and no words or phrases allowed to unveil the quitessential heart/mind to restore it to its original self.

The Ox and the Oxherder are both forgotten - break away from personal attachments to reach a stage of a unison between the inner self and the external world.

What is the relationship between our consciousness and the physical world? The world is born out of our consciousness en mass, as is our thinking and feelings. The mountains and rivers and the vast land area, the cosmic world, and all the stellar existence and beings are born out of our heart and mind, Consequently, the arising of our ideas and thoughts all exercise an impact (like the butterfly effect). Logically it follows that natural disasters such as wildfires and floods, even earthquakes, are creatures of our collective karmas.

Thanks to the cerebral functions we take the world for all there is and we pursue material and spiritual satisfaction all our lives, believing in everything we see, hear about, and think of. We have an opinion about everything and we set ourselves many limitations besides imposing our game rules on the others. Actually, this world as is and what we perceive are all brain child as the projections of our attachment. They are all creatures of our cognitive consciousness as expressed in the famous Buddhist quote of an epigram - ‘All things contrived are like dreamy illusions and shadowy reflections of bubbles; And as dewdrops or lightnings, they should be regarded as such.’Accordingly, the visualization of void and emptiness are all dream-like. The thing is - how do we come out of it?.jpg)

Once the enlightenment reaches the heart/mind and pierce through our ego-centric attachment, the Dharma attachment begins to slowly chip away bit by bit until ‘both the herder and the ox are forgotten’. In the case of an arising heart of purity, it means the world gets cleaned up and the confrontation between our purifying consciousness and the external world gets crushed to unify the self and the world as one with both as void. When the self no longer exists, life and death become irrelevant and a self-liquidating liberation prevails. The stage when both the herder and the ox are forgotten literally goes to say that the ox is a manifestation of the self, and the herder is the experience with the awoken and conscious state of mind of a practitioiner. Since the existence of the self has been experienced, an existential juxtaposition with the self disappears and an absolute unison emerges, along with all individual and objective cognitions. Consequently, neither the ox nor the herder is perceived, there is neither the subject nor the object, but the subject and the object fused into one unison for an existence that is fulfilling, satisfying, maximizing, and thorough-going.

Arriving at the stage of ‘both the herder and the ox forgotten’and with ther help of the anecdote of ‘a monastic practitioner who stole a lotus flower’, people begin to see the value of life's purity. Forgetting both the herder and the ox puts a label on the era when the outside world becomes obsolete and the age of communication and dialogue begins. Of the Ten Oxherding stages up to the point of riding the ox home, forgetting the ox with only the herder left alone in our cognition, then further to the stage when both the herder and the ox are forgotten. ‘Both forgotten’refers to both a visualization and an obliviation, and, voila, the person with the heart/mind no longer poses any obstacles (enroute of advancement).

Dharma Master Hsin Tao once said that ‘constructions should live in the big Nature’ and buildings on the Ling Jiou Mountains all consistently follow the principle of blending into the original mountainscape to become part and parcel of the ‘homestead’ habitat for the indigenous animals and plants. Why is it possible to discover such a diversified ecosystem on the LJM premises? The answer lies with LJM's respect for Nature reflected in how its buildings nestled nicely in natural settings without inflicting damages to the natural landscape and ecosystem to the extent that it lends itself as a perfect expression of ‘the subject and the object mutually forget each other and they both become one with all forms of existence’. On that note one can't help but ask - isn't that the best possible manifestation of ‘both the herder and the ox are forgotten’?

●Let's go searching for the ox together

→The Patriarch's Hall and the Fa Hwa Cave (Rock formation in the shape of an eagle's head)

→The Sacred Founding Hall

► Download the digital calendar entitled Visit LJM for Meeting the Inner-Ox

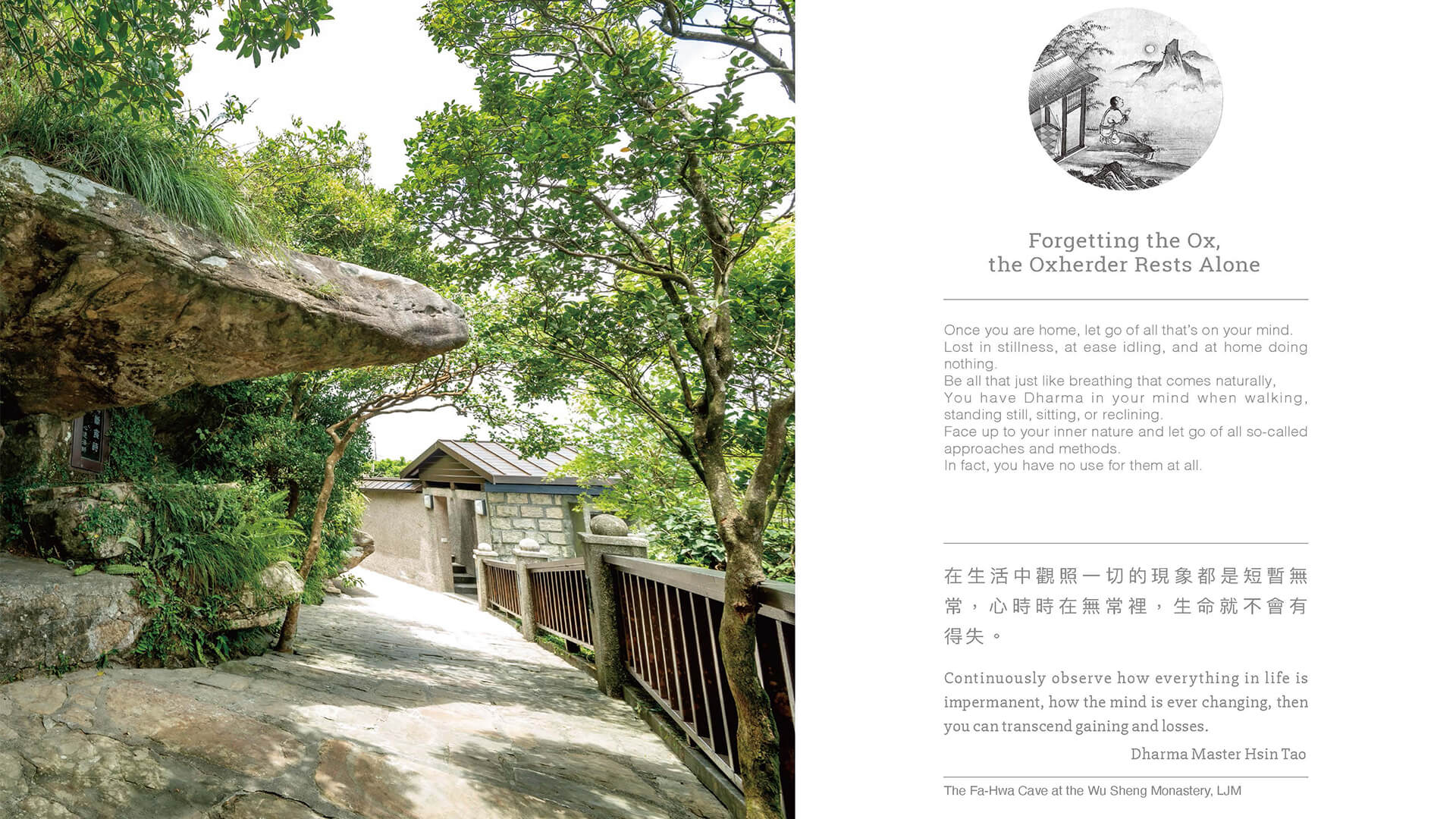

Forgetting the Ox and the Oxherder Rests Alone

.jpg)

Forgetting the Ox and the Oxherder Rests Alone

The oxherder reached home. The ox has gone away so that the herdsman is no more busy at all.

Still in bed and dreaming with the sun already high on the sky, the oxherder's whip and bridle idle aimlessly in the storage room.

'Reaching home' refers to one seeing his intrinsic nature when arriving at the spiritual mountain, the home of Bodhi Nirvana. By this time the oxherder already comprehends that the ox is actually part and parcel of himself: there is no ox other than the mind and thus accordingly, the ox is the awareness of the present thought.

'The ox has gone away so that the herdsman is no more busy at all' suggests that awareness of the thought is nature-born and there is actually no ox to herd and no ox to get. It is no longer necessary to train and sharpen one's awareness by virtue of a corresponding object. One is best advised to let go of even such awareness to be a plain free-of-all.

Getting up late and having the whip and bridle idle around recreates the scenario that the herder has returned home and realized that it is nothing with the oxherding, it follows then that the whip and bridle are no longer needed and they could be spared altogether. The fact that one can easily afford to stay in bed for long hours suggests that from now on any movement one makes in his daily life- from getting dressed, having a meal, to the sheer action of walking, living, sitting or sleeping- would be practice of the Dharma, .

Forget the ox and the oxherder rests alone- Take life as it is that there is nothing to form attachment

Once upon a time a butcher made provisions as alms to support a monk, yet the monk did not share Dharma with the butcher. As karma would have it, the two again befriended with each other in the next life. Once the butcher ran out of money for business and the monk loaned him the money with the condition that the butcher must supply produce unconditionally when the monk demands it. Then it happened at a time when all slaughtering was banned for three days out of respect for the birthday of Avalokitesvara. Decapitation awaits any violators of the rule. The monk demanded half a pound of meat from the butcher, but the latter pointed to the ban for an excuse. The monk then said they could meet half-way and the butcher can just cut some meat from his own body to honor the commitment of their pact. The butcher bemoaned the request and said that the pain would be excruciating and too much to bear. The monk looked him in the eye and said, ‘now imagine how the animals feel to come under the knife’. The butcher was jolted by a shock that also awarded him with sudden enlightenment. He dropped everything and left to practice Dharma with the monk, and attained the status of an Arhat at the end. The story bears the name of ‘Putting down the slaughtering knife to pursue Buddhahood thereupon’. .jpg) A man of many vices can repent in a moment's realization that he'd want to right the wrong and make amends for the future. The man can pledge a vow and embark on a journey of attaining Buddhahood. In reality, not everyone is a butcher, and the butcher's knife stands to symbolize people's own confusions, delusions, preferences, and fixations. When the herder reached home and forgot the ox he rode, the anecdote suggests that a religious practitioner is free from worries, judgments, and wanton desires. The troubled mind is no more and the trouble-free person no longer picks apart the realms inside or out. No qualm of fixations, but perfectly aware of one subjective self. When all delusions disappear, the original nature emerges as absolute clarity with a perfect see-through. There is no description in any words when the Buddha nature emerges, because it prevails both in- and outside. A fish in water doesn't make much of the water, as do we with the air we breathe that is largely ignored by our conscious mind. The herder sans the ox is thus by now a person free of worries in the mind.

A man of many vices can repent in a moment's realization that he'd want to right the wrong and make amends for the future. The man can pledge a vow and embark on a journey of attaining Buddhahood. In reality, not everyone is a butcher, and the butcher's knife stands to symbolize people's own confusions, delusions, preferences, and fixations. When the herder reached home and forgot the ox he rode, the anecdote suggests that a religious practitioner is free from worries, judgments, and wanton desires. The troubled mind is no more and the trouble-free person no longer picks apart the realms inside or out. No qualm of fixations, but perfectly aware of one subjective self. When all delusions disappear, the original nature emerges as absolute clarity with a perfect see-through. There is no description in any words when the Buddha nature emerges, because it prevails both in- and outside. A fish in water doesn't make much of the water, as do we with the air we breathe that is largely ignored by our conscious mind. The herder sans the ox is thus by now a person free of worries in the mind. .jpg) For the previous picture of ‘Riding the Ox home’, there was the oxherder and the ox, which stand for a mind to tame and a goal yet to achieve. The existence of the subject- the herder- and an object that he wants to tame demonstrates separation of Dharma practice and the expected realization. The present picture ‘Forgetting the ox and the oxherder rests alone’serves to remind us that even a God-forsaken sinner could still get on to the Pure Land of Amitabha if he can recite the name of Amitabha non-stop in his final moment - because his final idea was for and about all sentient beings except himself.

For the previous picture of ‘Riding the Ox home’, there was the oxherder and the ox, which stand for a mind to tame and a goal yet to achieve. The existence of the subject- the herder- and an object that he wants to tame demonstrates separation of Dharma practice and the expected realization. The present picture ‘Forgetting the ox and the oxherder rests alone’serves to remind us that even a God-forsaken sinner could still get on to the Pure Land of Amitabha if he can recite the name of Amitabha non-stop in his final moment - because his final idea was for and about all sentient beings except himself.

●Boulderstones worthy of your exploration

→The Fa-Hwa Cave

→The LJM Founder's Hall

► Download the digital calendar entitled Visit LJM for Meeting the Inner-Ox

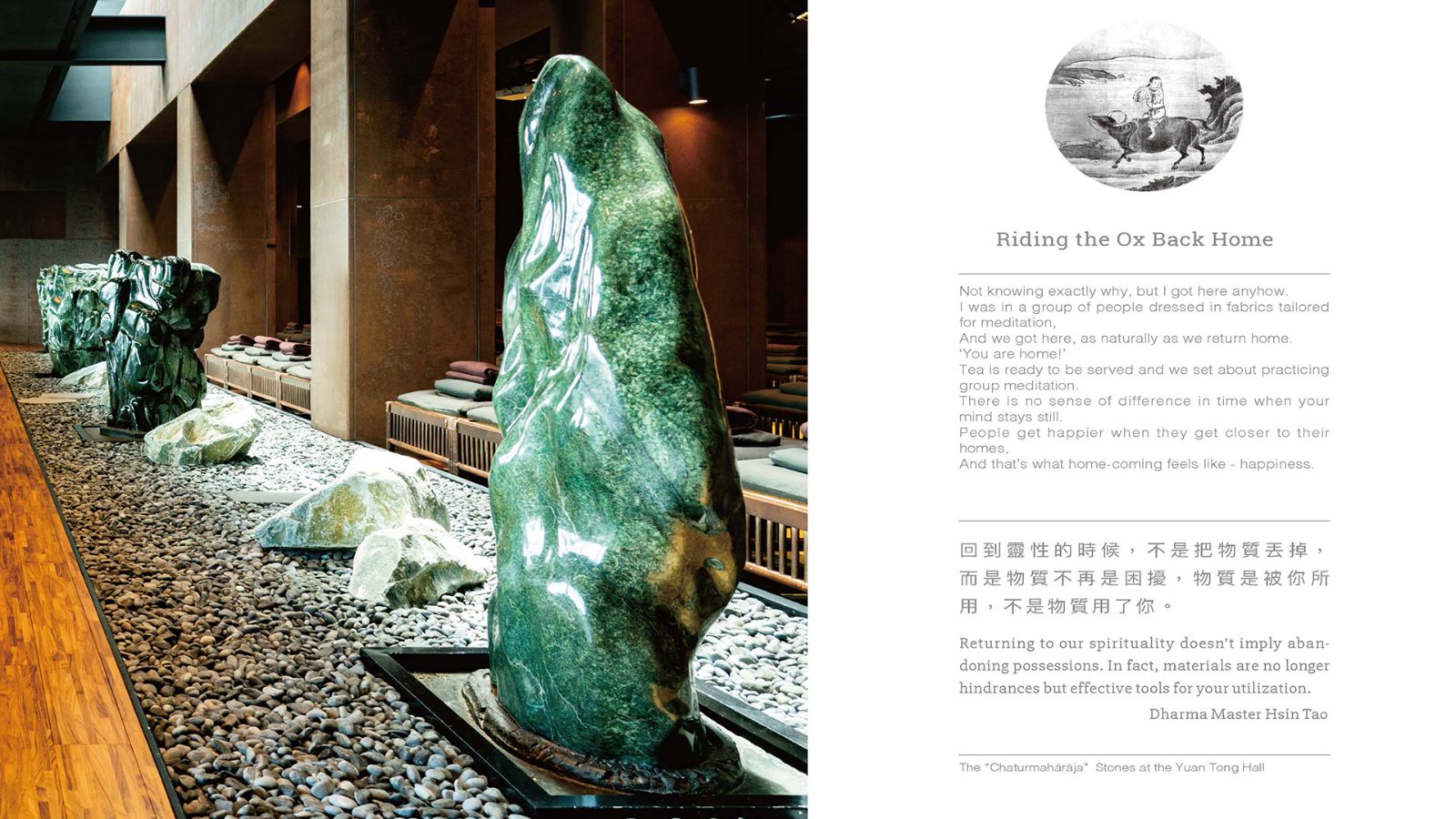

Riding the Ox Home

Riding the Ox Home

Riding the ox home in relaxed strides, sending off evening clouds reflecting the sunset with a piccolo melody;

The clapping and the tune already manifest the unlimitedness of the Buddha-realm, and those in-the-know have no use for music playing.

The herdsman in the picture of Riding the Ox Home is seen riding a tamed ox home. The ox reins casually attached to his waist, his hands were free to hold up a piccolo and play a melody easy on the ears. ‘In relaxed strides’ suggests the long journey between the phases ‘in search of the ox’ and ‘taming the ox’ affords the realization that the non-arising nor ceasing Dharmakaya which comprehends tathātā and its functioning is the ultimate ‘home’. All the hard work of training in passing all challenges of body, mind, and soul paid off and it is suggested by the ox reins casually attached instead of being wielded. It's an easy ride home, as the wandering mind has been ‘reined in’ and can roam about freely. The herdsman is now just one step away from arriving at the ‘home of the original nature’ that embodies the Buddhahood attained.

A piccolo melody sends off the evening clouds reflecting sunset refers to an appreciation of the realization that takes in the beauty of the landscape and the melody of the piccolo in the setting of a sunset for a delightful sight. It is a moment when the man, the ox, the piccolo, and the sunset all fuse into oneness. The mind and the surroundings are in harmonious sync in reaching the home of intrinsic nature that knows no difference. At this point of practicing Dharma, the cognitive mind is full of bliss, unlimited luminosity and enormous delight. Celebrations are indeed called for.

'The clapping and the tune manifest the unlimitedness of Dharma' is a verse that means once the mind attains Bodhicitta, the moment's clapping and tune unfold to show the unlimited wonders of Chan/Zen. Otherwise, the clapping and the tune are mere attachments of a cognitive mind that desires, resulting in unlimited arising and ceasing and the frustrations thereof.

'Those in-the-know of the music scores have no use for music-playing on the piccolo' goes to suggest that for those who are in possession of true knowledge, no further words would be necessary as laid open by the expression that ‘the silence speaks volumes’. The clapping and the tune, after all, are functions of the mind that inevitably arise and cease. Only when all sounds become silent and the arising and ceasing becomes non-arising nor ceasing, one can then reach enlightenment. The well-known story of how Buddha held up a flower in his hand and his disciple Kasyapa smiled lends itself beautifully to illustrating that words have no place in the case of sudden enlightenment.

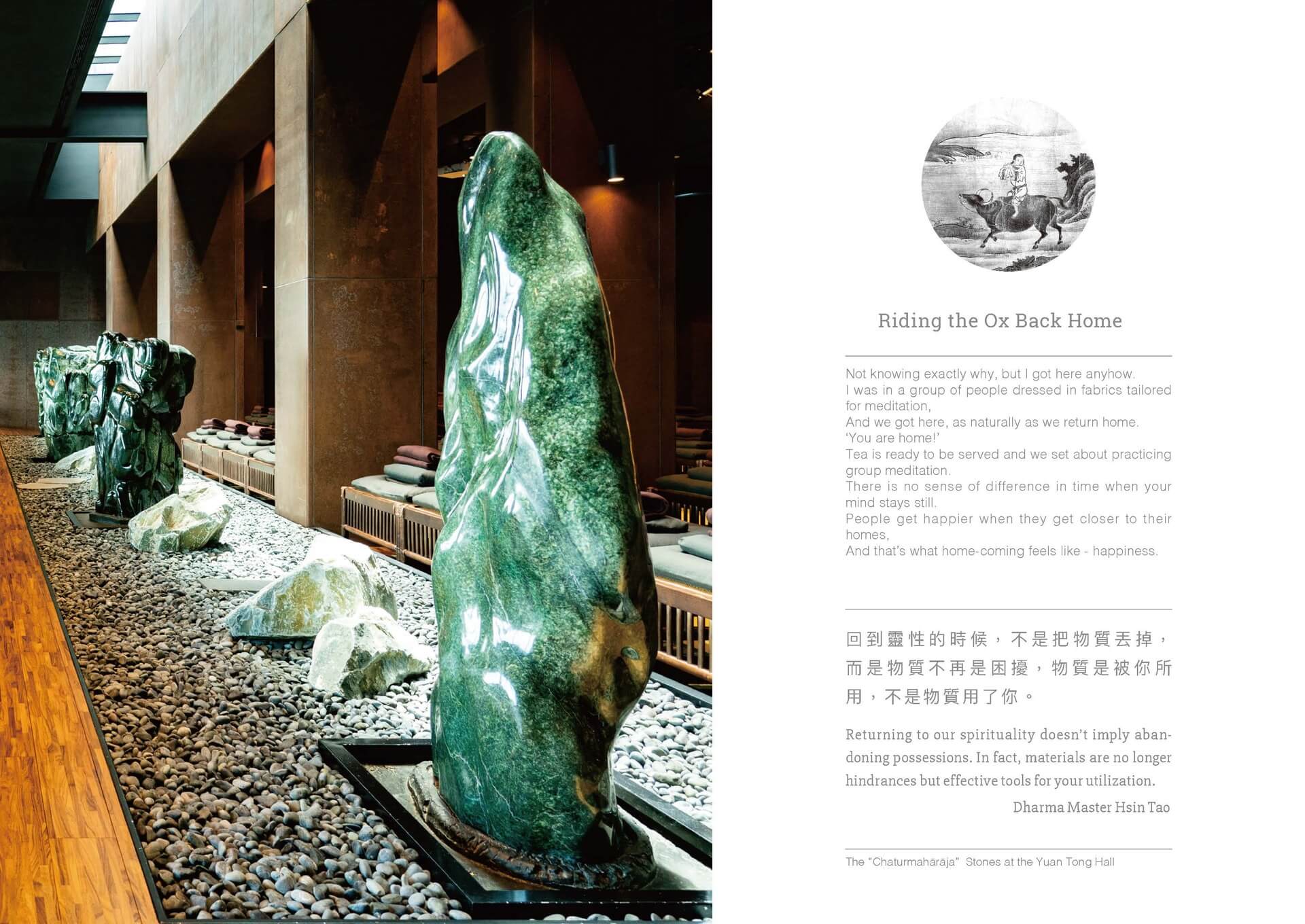

Riding the Ox Home - A well-rounded, warm stone

Our mind goes after what it desires for possession, turning down those they dislike. Headaches and issues thus occur in our daily life. Suppose we train and manage to keep detached from the external world and recall the minds that usually become easily attached to break them in, we then remain free of outside influence and keep clear-headed at all times in all places. Thus we are our own masters devoid of hindrances.

With ‘Riding the Ox Home’ we are now on painting number six of the Ten Oxherding series. After some training over time, we have been relatively better at oxherding. The ox and the herdsman now have agreed a truce to leave earlier stages far behind. When the mind is ‘fine-tuned’, all our troubles with the wanton desires will be resolved and ‘reined in’. Ever so gradually, we claim back our inherent clarity. ‘Taming the ox’ suggests our way home, and back to our original nature that remains non-arising nor ceasing. Along the journey the herdsman rides the ox comfortably and plays a tune with the flute. Both man and ox are in unison and homeward-bound, going in the same direction and at the same tempo in sync. All the agonies and pains imposed by the training are now cast away to afford a genuine appreciation that is only possible when you find yourself in a rhythmic unity with the cosmos - a truth of returning to life itself that practicing faith empowers.

During the earlier phase of herding the ox, we trained to have our mind softened and pliant. And with ‘Riding the Ox Home’ we are reminded by the story of the ‘Well-rounded and warm Stone’. When the pebble in our hands gets warm, so do our minds. Your hands are as warm as the stone feels, as you are happy. When our mind becomes softened, we ought to reach out to extend warmth to others, because life is about helping one another and about the linkage of warmth. The sentient beings are your quilt in coldness. You radiate and give warmth, and it bounces back. Once the compassion for sentient beings arises from within you, it is a sign that you have tamed the ox and you are getting ready to ride it home. Our modern-day case in point is a likened scenario with us coming to the Yuan Tong Hall, where we offer tea to one another and rejoice in taking our seat for meditation to bask in a sheer bliss and savor the sweetness of home-coming. The warmth heals and our delight grows deeper, the closer we inch toward our ultimate home of the mind.

● Let's go looking for the Ox together

→ The Hwa Dzhan Hai Main Hall, the Yuan Tong Hall

► Download the digital calendar entitled Visit LJM for Meeting the Inner-Ox

Tending the Ox

.jpg) Herding the Ox

Herding the Ox

Whip and rope as a permanent fixture to curb 'it' from wandering into dust and dirt of any worldly entanglement.

Once the mind begets purity and peace, chains are no longer needed as 'it' will keep to our Buddha nature.

To herd the ox is to keep an eye on it at all times, and use the whip and rope to rein it in if it wanders off. To have the “whip and rope as a permanent fixture” is a metaphor that suggests exercising repentance and determination in the practice of perception and recognition to steady the mind from wandering off into wanton desires.

The ‘it’ in the poem refers to that wandering thought. Dusty worldly entanglement points to the six senses of vision, sound, smell, taste, touch, and mind, the ensuing fixations, wanton desires, and vicious prejudices. To curb ‘it’ from wandering into dust and dirt eludes to the fear that the wandering mind might jump at those wanton desires so much that our mind would be marred like a mirror getting dusted and lose its impeccable reflection of illumination.

For the mind to achieve purity and peace the herdsman keeps the ox reined in with the whip and rope and keeps it from grazing the meadows of other people. This is the stage of the process of ‘domestication’ where the ox is tamed and grazes properly. It no longer shows stubbornness and that means one has overcome the innate attachment, anger, and ignorance, and no longer sees or hears external temptations for the six roots to gradually steer away from the six senses. The discerning mind retains its forever calm regardless of the objects of vision and sound.

The last verse of the poem is a stark contrast of the ox before and after its taming: whereas whip and rope were the herdsman's tools to keep the ox under control while grazing, such tools are no longer necessary as the ox has become tamed and thus a self-evictor of the heart whenever wanton desires arise. It goes where the herdsman goes and no longer wanders off.

Herding the ox marks a particularly challenging stage in the ‘Ten Oxherding’ scroll of painting for practicing Chan meditation. Tools would apply until we accomplish the goal of mind-taming, making our mind inseparable from the one of Buddha's. Constraints like whips or chains are unnecessary then as every thought will side with the trained mind. The practice of discipline, however, needs to be an integral part of any and all Buddhist practitioners, because ‘old habits die hard’ and even seasoned Buddhists may improperly obstinate and discern whenever the vigil wanes. Even Master Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch of Chan Buddhism, continued to practice ascetics 15 years after attaining enlightenment. But how do we apply such a practice of discipline in daily life? We cite the verses from the Lotus Sutra's Universal Gate Chapter on Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva that ‘Hearing his name and seeing his form, Keeping him unremittingly in mind, Can eliminate all manner of suffering’. That goes to inform that people are best advised to resort to chanting the name of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva and remain undeterred with passing events and all fleeting things no matter what. Keep up such practice until our Buddha nature regains and you are finally free from any ego-centrism and any arising desires thereof.

Tending the Ox: The Old Monk & His Heart-Resting Stone

Dharma practitioners are often faced with obstacles, among which a sense of fatigue is the most common and frequent. A rare and occasional sense of achievement is apt to bring an abundance of delight bordering on ecstasy to create a false impression that all hurdles have been mitigated, with a self-righteous arrogance ensuing. Only too quickly disappears that sense of achievement into thin air.

Chan Master Shih Gong had been a hunter until he achieved enlightenment upon understanding the sermon Master Ma Tzu was preaching. The huntsman laid down his arrows and bow to seek refuge in the Three Jewels. After a while, Master Ma Tzu asked him about his practice, now that he no longer hunts. Master Shih Gong replied that he spent his days herding. Master Ma Tzu pressed on and asked how. Master Shih Gong said that the ox would get ‘dragged’ back whenever caught grazing. Upon that, Master Ma Tzu said ‘now that's herding.’ Once enlightenment is achieved, the enlightened awareness will be the sole yardstick to measure whatever that goes on inside your mind or outside your body in the immediate surroundings. Make sure that the awareness is always present and ‘drag the ox back whenever catching it grazing’, keeping us vigilant and undeterred as the ox we herd is our mind.

Throughout this phase of oxherding, the tools of whip and rope are at hand to break in the cow that grazes whenever possible even on other people's pastures. The moral goes to emphasize that discipline needs to continue even after achieving enlightenment. Because whenever the guard is down, people are apt to skid back to the troubles and worries of the past..jpg)

It goes without saying that the ox will wander and indeed, ‘old habits die hard’. But if we stay alert and put our awareness to good work, it'll all be like a dream that disappears when we wake up. Now, in the present phase of oxherding, we borrow from the anecdote of ‘The Old Monk & His Heart-Resting Stone’ to remind ourselves that we mustn't ever forget about our natural gift of a clarity that is pliant in elasticity just like water that is formless and its flow can re-route itself when hitting a mountain or a boulderstone. In a similar fashion, if the mind can be like water that effortlessly adapts to conform with the teachings of Dharma, our mundane troubles and worries will disappear naturally.

► Download the digital calendar entitled Visit LJM for Meeting the Inner-Ox

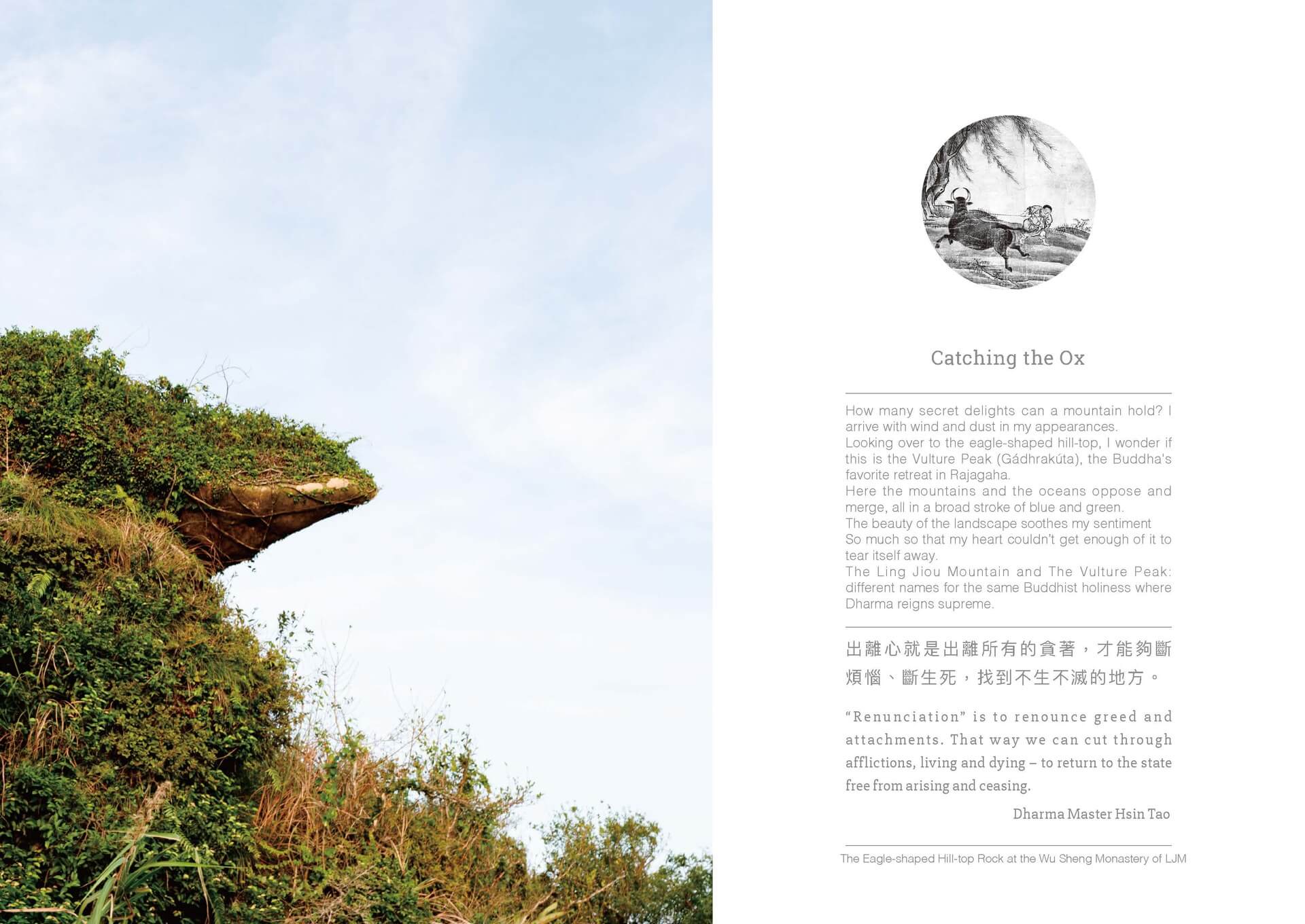

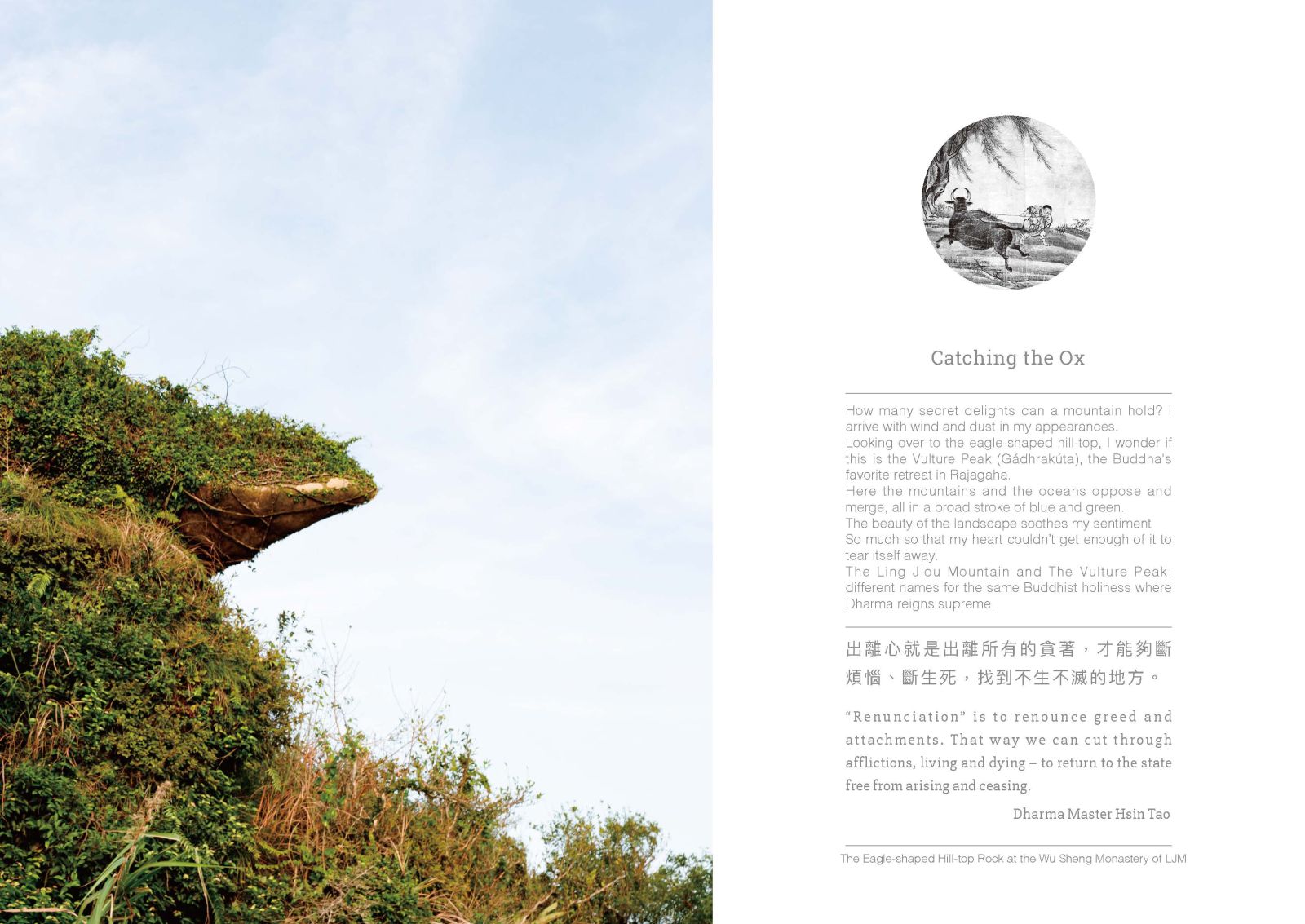

Catching the Ox

.jpg)

-Catching the Ox-

Done the utmost might to secure your control, knowing full well that the ox possesses a strong mind and a powerful physique.

There are times in the learning curve when you just barely made it to the high plateau, and already finding yourself stuck anew deep in misty clouds.

The opening verse of the poem refers to the sweet fruit of hard toils in the process of Dharma practicing to one's maximum might: once the enlightenment is achieved, a genuine flow-through linking all senses ensues. And thus accordingly, the ox (meaning our thought) possesses a strong mind and a sturdy physique and “it” actually has always been part and parcel of our nature already. It is there, ubiquitously, and there is no avoiding it but to shoulder and live with it.

‘Making it to the plateau’ describes the state of mind with enlightenment and likens it to the scenario where a quality incense with its aroma accompanies the practice of meditation and there is but clarity and serenity - as if you'd be standing atop a high plateau, with the receding horizon blending into clear skies. And ‘finding yourself stuck anew deep in misty clouds’ sums up the elusive and unstable state of early enlightenment. There are moments when you know the awareness is at work, but it has no lasting stamina, and sooner than you reckon, it's gone and your senses would be cloudy again. Up to this point, it is clear that the domestication process is both time-consuming and patience-demanding and the continued practice of discipline is a quintessential requirement for ‘catching the ox’ to mitigate the common complacency that often arises.

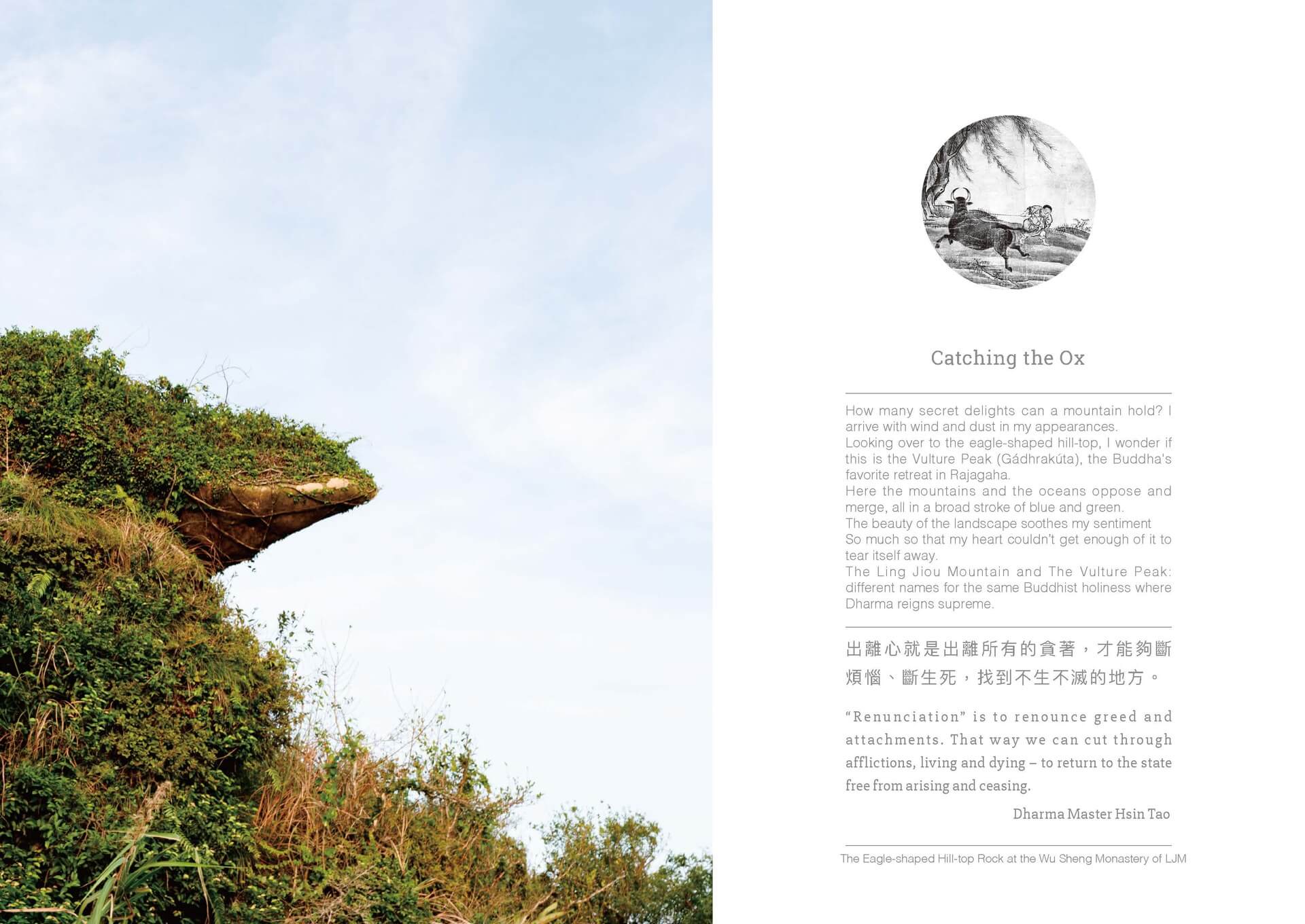

Catching the Ox: Boulderstone Resembling Buddha's Mentor

One of the most celebrated scenic spots of Ling Jiou Mountain(LJM) is a natural rock formation in the shape of a falcon's head, and the boulderstone is situated right behind the Patriarchs’ Hall at the LJM Wusheng Monastery. It strongly reminds people of its counterpart in India, where Buddha shared the Dharma of prajna, and the vibrations of the resonance (meaning the frequency of the magnetic field) the two spots echoing each other create. The LJM Vulture Peak further has a nearby accompanying site known as the ‘Stupa of the Buddhas of the Three Times’ and together, they seem to remind people of the core value of Buddhism expressed in the following phrase: ‘To keep away from all evil, cultivate good, and purify one's mind is the advice of all Buddhas.’ We venture to interpret that as advice of the Golden Mean for the practice of ‘Learn as you do’, in order that a balance can be struck between ideals and realities for people who study and practice Buddha Dharma can find firm footing in their balanced daily life.

There are Buddhists who envisage themselves in a surrealistic milieu and view the World of Ultimate Bliss in the West as their utopia. Theoretically, there can be no finger-pointing thus accordingly, yet the dire fact is that the divide between ideals and realities in daily life is simply too wide for them to cope with. A case in point can be seen in a senior volunteer of LJM, whose routine contains basically two elements: she looks after her grandson Monday through Friday and performs voluntary tasks for LJM on the weekend. But every time the two segments overlap and cross over, she'd debrief her family and her fellow volunteers down to the last details to facilitate the handover. She does that because Dharma Master Hsin Tao once said that it is important to have one's own home well taken care of, so that the path of studies to enlightenment can be as barrier-free as possible. A famous quote from the Dharmic Treasure Altar-Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch roughly translates into the following -- “The Buddha Dharma exists for the world, Apart from this world, there is no enlightenment. To seek bodhi elsewhere, Is as futile as looking for horns on a rabbit.” Putting two and two together, and the moral of the LJM volunteer's story is that daily chores represent the flipside of her voluntary work for other people outside of her own family, yet it is equally meaningful as far as exercising self-discipline is concerned to deepen the appreciation of the practice itself ‘as a tool to rein in and/or drag back the ox whenever caught grazing’.

The practice of Dharma is a personal undertaking and we must resolve our own issues before we can reach out to help others. To strike a balance between the practice of Buddhism and daily life is, with no stretch of the imagination, a practice of discipline in itself. By this time and at the stage of ‘Catching the Ox’, we would want to point to the fable of the ‘Boulderstone Resembling Buddha's Mentor’ for an analogy to remind everyone that it is equally important to master the ethics of Confucianism and the minimalism of Taoism and practice these alongside the Dharma of Buddha in both the spiritual realm as well as in the secular world. Just like controlling the ox by the rope, neither too tight nor too loose. Practice the Golden Mean to maintain clarity in the presence at all times and that balance between ideals and realities best describes what ‘Catching the Ox’ is all about.

► Download the digital calendar entitled Visit LJM for Meeting the Inner-Ox

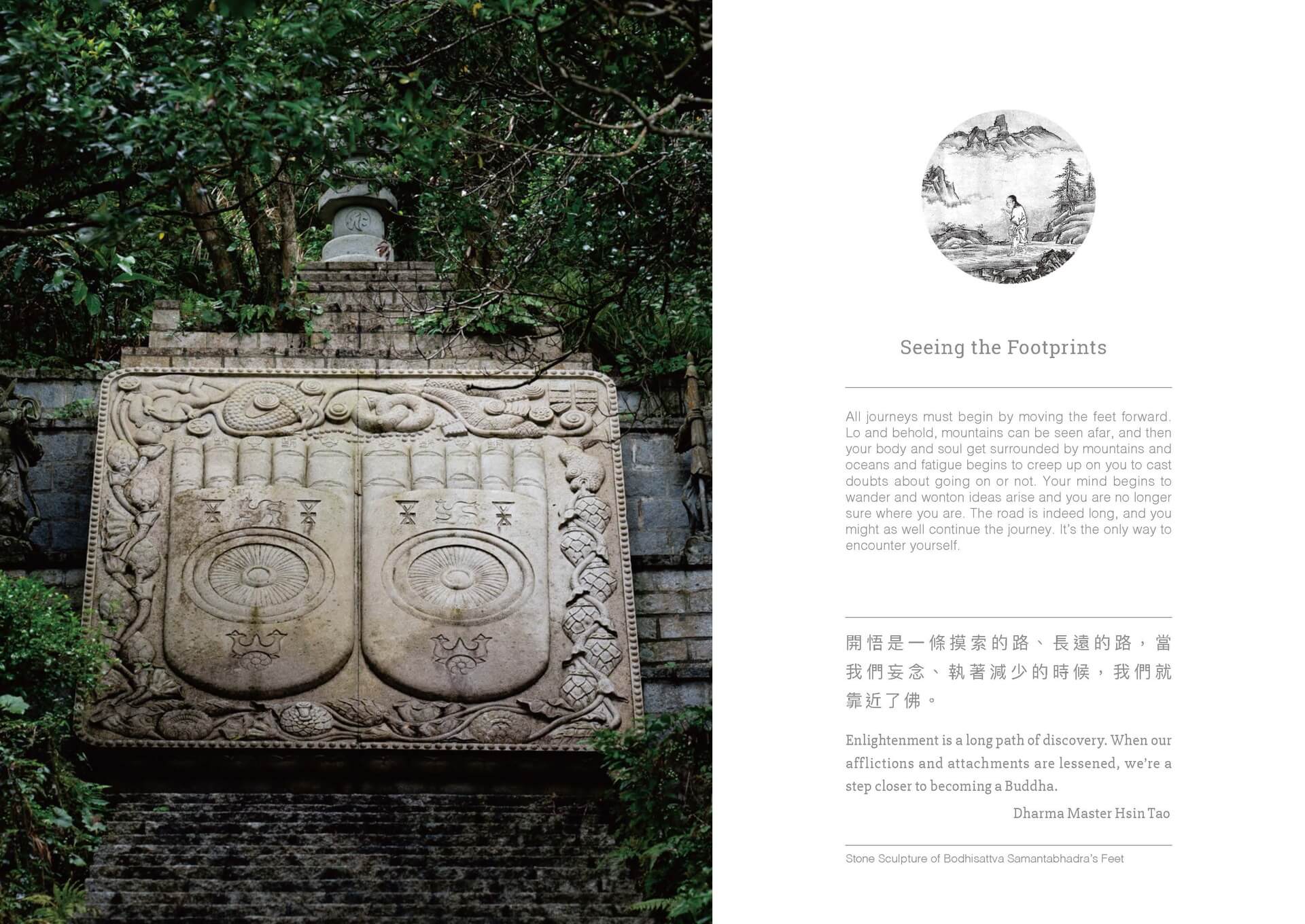

Seeing The Ox

.jpg)

Traces abound in the woods near the water,

Aren't trampled grass clues obvious enough?

Even in the deepest of remote mountains,

The flaring nostrils debunk its hideout.

The accompanying poem to one of the pictures of the Ten Oxherding collection - “Seeing the Footprints” in the present case in point - deciphers the metaphor. The first phrase of the poem refers to the backdrop where meditation was being practiced in an effort to attain enlightenment. There are suggestions that the practitioner could be on the right track in his pursuit, but not with certainty. Hence, 'traces' abound.

Trampled grass reveals footprints of the ox without pinpointing any certain direction where the animal went astray. The Dharma practice of meditation gives rise to an idea that helps to reverse what troubles the mind and the ignorance to finally make room for mindfulness, and trampled grass wasn't an eye-sore anymore. While traces of the footprints do point to the right way of achieving enlightenment via meditation, it would be premature and complacent to stay put. The search for the ox must continue.

The third phrase makes reference to the process and stages of practicing meditation, in that repeated elevation of the consciousness affords increasingly deepening awareness and clarity of all relevant details. The unfolding revelation reaches all eight levels of the consciousness that one realizes how infinite our thoughts have developed and expanded for numerous lives as if it contains everything of the universe. One is all, and all is one.

The ‘flaring nostrils that reach the skies’ suffice to describe how big the ox's nose is, implicating the vastness of our thoughts. The thoughts reveal everywhere, thus they can be seen, be heard and be smelt. For human beings, thoughts are inherent just like the five sense organs including the nose.

The accompanying poem and its interpretation as shared above roughly depicts the milieu of Stage Two “Seeing The Footprints” of the Ten Oxherding pictures. By that it means that some initial result of practicing meditation becomes tangible, and the practitioner is inching towards comprehending the big picture from angles such as the juxtaposition of objectivity versus subjectivity, or that all phenomena are nothing but variants of perception of our “inner ox.” The search must go on, therefore, as there are only footprints to be seen, not the ox itself.

Seeing Footprints of the Ox - Boy Monk and the Stone-for-Sale

Buddha was said to have made the remark that the Pure Land Tradition is a Dharma Gate (methodology) hard to pry open, as it was commonly believed that reading Buddhist scriptures and citing Buddhist quotes equals appreciation of Dharma. The truth is, however, that to understand the text of Buddhist scriptures warrants only a superficial understanding and that is a powerless knowledge. The other form of comprehension is an awakened recognition that can be referred to as ‘enlightenment’that affords prajna, which is wisdom with power.

Those firmly converted followers who practice Buddhism in the footsteps of Masters and Grand Masters are often encountered with challenging adversities that lead to doubt, confusion, or even desertion if not quickly helped and amended. Many work hard in their studies of Buddhism, but then relax often and tire easily, or jump ship altogether - because there is no reassurance that their journey is on the right path in the right direction. There are folks who become well versed in a religious setting after only a relatively short period of Buddhist studies. In most cases such people grow to believe that they truly understand Buddhism without realizing that they stay stuck in the phase of ‘Seeing Footprints of the Ox’and wide of the mark of enlightenment. Whoever without attaining enlightenment have but wanton desires as the form or phenomenon for any of their thoughts and ideas. The phenomenon of food pops up in the mind when the thought arises, and it gets replaced by that of a loved one, when the thought of the latter arises. The phenomena arise and cease, and replace one another in a constant train of thought. When the query of ‘Who chants Buddha’s name?’arises, a non-phenomenon doubt arises to expel phenomena-based thoughts and the external universe ceases and you become unconscious both physically and meta-physically. Gradually and over the time, only the non-phenomenon purity remains in the total absence of any wanton desires.

Whoever without attaining enlightenment have but wanton desires as the form or phenomenon for any of their thoughts and ideas. The phenomenon of food pops up in the mind when the thought arises, and it gets replaced by that of a loved one, when the thought of the latter arises. The phenomena arise and cease, and replace one another in a constant train of thought. When the query of ‘Who chants Buddha’s name?’arises, a non-phenomenon doubt arises to expel phenomena-based thoughts and the external universe ceases and you become unconscious both physically and meta-physically. Gradually and over the time, only the non-phenomenon purity remains in the total absence of any wanton desires.

The saying goes that all journeys must begin with the first step, which means as long as the practitioners persist and remain steadfast with the ‘Practices and Vows of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra', traces of direction will eventually be detected from among the confusing footprints left by a bewildered ox. We find ourselves in the stage of ‘Seeing the Footprints of the Ox’and the point is to experience what practices bring about that will further cement our faith. Meanwhile, the story of the boy monk with the stone for sale sheds light on the significance of the lessons of ‘Value vs Price’and ‘Staying the Course’that elevates the search for the meaning of life to the creation of value for life.

► Download the digital calendar entitled Visit LJM for Meeting the Inner-Ox

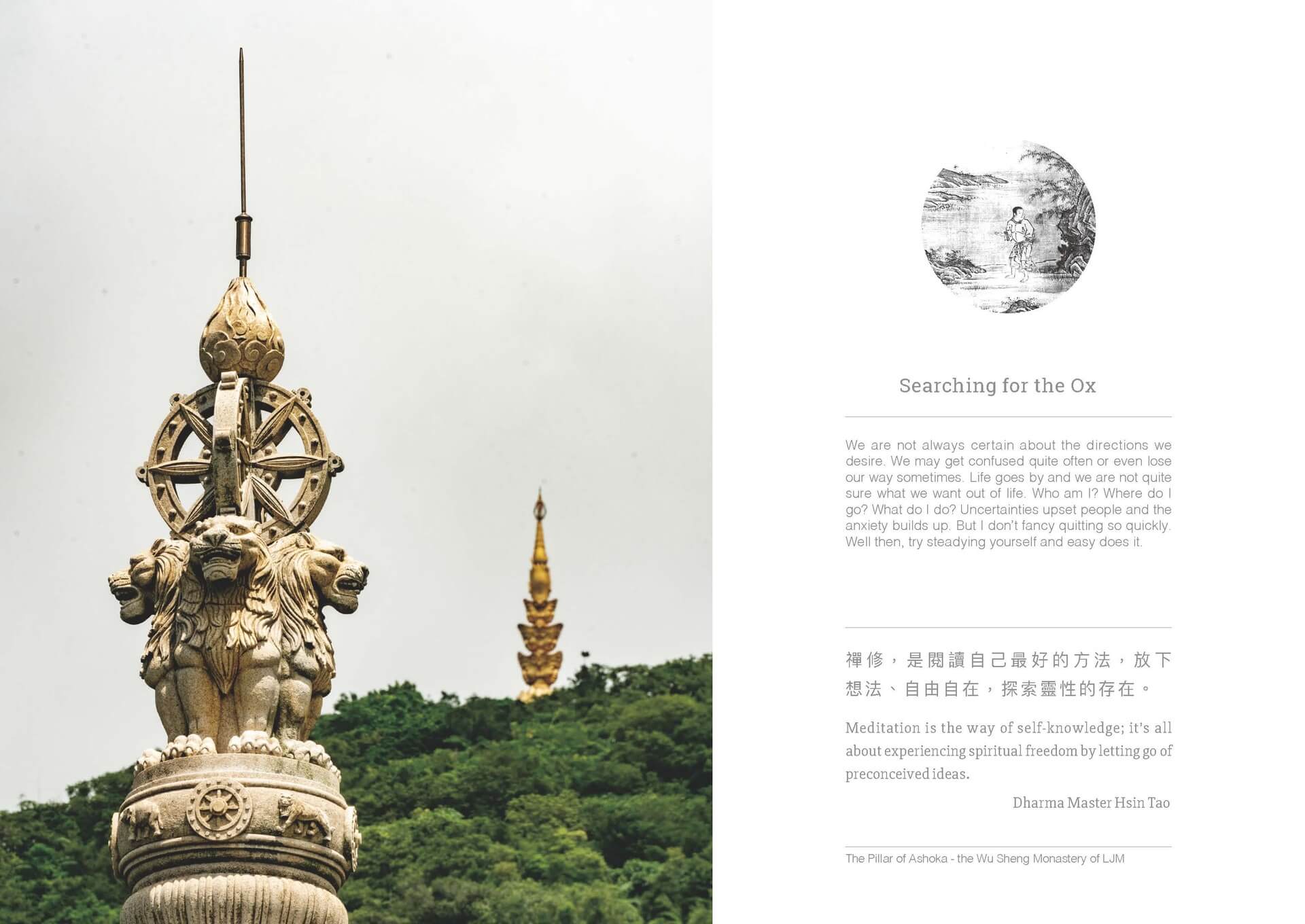

Searching for the Ox

.jpg)

Hasty chase through grass thick and long, the road winds deeper into remote mountains across wide waters;

Exhaustion and fatigue to no avail, only cicadas are heard atop maple trees against the dusk.

The Inner-Ox actually refers to the true Self as the essence of life itself, and the ‘Searching for the Ox’stage is when commitment to the pursuit of the Way is pledged. The Inner-Ox (the non-phenomenon Self) is never really lost, but becoming increasingly distant and cut-off from the original Self due to the lack of self-awareness. The Inner-Ox became gradually submerged and drifted further away from the original Self. And since it is never really lost in the true sense of the word, to look for it would be an oxymoron. Just remember that all journeys must begin with the first step.

The thick and long grass is a metaphor for wanton desires, worries, and ignorance, and by separating the grass it suggests the effort in searching for the ox to symbolize the pursuit of Buddhist studies. Put succinctly, to look for the Inner-Ox in a physical world made of the four basic elements of earth, water, fire, and wind, it necessitates the persistent quest to always cut to the chase and ask questions like ‘who is it that keeps chanting the name of Buddhas?’, and ‘who is it that is now savoring tea?’

Remote mountains suggest that holy grounds are afar and across an infinite body of water in our imagination, just like the road that ‘winds further deep’into the distance in search of the Inner-Ox. Ever since the beginning of time in mankind’s collective memory, an infinite and limitless amount of seeds have always been in store in the eight realms of cognition and awareness. The more topical discussions we go for, the deeper and wider the realms of awareness and cognition turn out to be, a field broad enough for the pursuit by anyone who has yet to attain enlightenment.

It comes as no surprise that many still have no idea who chants the name of Buddha and have yet to locate the true Self at the cost of total exhaustion after relentless effort. You chase after the truth to the point when you find yourself entirely engulfed in a cloud of confusion and doubt. No wanton desires, no drowsiness, and the whole world has become obsolete with past, present, and future all non-existing, it is a scenario of stable continuum and nothing but the quest to probe, to ask, to reason and to comprehend exists. When there are capabilities and resources to fall back on, such determination for the pursuit will not be possible. You will never see the ox no matter how far you look from riding on top of it. The effort in lookin for the Inner-Ox is nonetheless a must, because only then it becomes clear that the capacities of our five senses are innate, whereas our consciousness needs to practice to sharpen and grow to finally push us and inch towards the ultimate enlightenment.

After a day’s hard work and search and nothing but the cicadas can be heard is a description that suggests toils over the time awards some initial appreciation of what the original Self could look like. You have a vague inkling, but not the confidence to claim that you got it. Thus it can be an experience shared by many in their initial stage of studying Buddhism. You believe you are somewhere along the path toward enlightenment, but not sure where exactly and how far yet from the destination.

The opening poem gives a vivid description of the state of mind of those on their way in search of the Inner-Ox. ‘Searching for the Inner-Ox’marks Stage One in the Ten Oxherding saga - comparable to looking for the meaning of life with an oversight of the original Self: you pry open the thicket of wanton desires of the secular world, using the five senses that our innate capabilities and process the data by the cognitive recognition of consciousness. Instead of looking away and outward, an inward self-examination would probably be a much better way to start. Again, remember that all journeys must begin by taking the first step.

In Search of the Ox - The Story of Three Stonemasons

All journeys must begin by moving forward and ours started 38 years ago, with Dharma Master Hsin Tao leading his disciples and followers in building the monastery from the ground up and with scratches. A thatched cottage served as the meditation hall for general retreats, a stone plate for the altar, and pre-fabricated cement templates covering the bare ground functioned as seats. All materials for the construction of the Patriarch Hall came from whatever was available and laying around and a stone structure was built to the natural slope of the mountain. Boulder stones on the Ling Jiou Mountain (LJM) have been constant companions to practicing masters and visiting laity from all over, creating touching stories in the course of time that can be likened to the famous Chan/Zen fable with the paintings of the Ten Oxherding. The ox is a metaphor for our mind that must be tamed strenuously with tremendous tenacity and wisdom in ways similar to how attachments and fixations must be overcome in the practice of Dharma by virtue of mindfulness. How come there are in our daily life frequent moments of restlessness, anxiety, a sense of loss and suffering? Why do many people lose orientation without knowing where to go next in life after years of hard work? Ideas flash through our mind the whole time, but which ones are truly ours? Where are the exits? How to make ourselves a better life? And what are some of the stages people go through in the course of taming the inner-ox? The herdsboy in the Ten Oxherding symbolizes the practitioner of Dharma, and the ox represents the inherent spirituality that he/she tries to restore. The ten stages of the herding depict the corresponding phases in our soul-searching journey. Patriarchs of Chan/Zen Buddhism cast the ox as a symbol of our mind, and to reveal the inherent spirituality, or Buddha Nature, we must herd the ox by prying open the origin of the mind. The Ten Oxherding is a sequence that points to the proper way of practicing Chan/Zen Buddhism with implied instructions applicable to our daily life.

How come there are in our daily life frequent moments of restlessness, anxiety, a sense of loss and suffering? Why do many people lose orientation without knowing where to go next in life after years of hard work? Ideas flash through our mind the whole time, but which ones are truly ours? Where are the exits? How to make ourselves a better life? And what are some of the stages people go through in the course of taming the inner-ox? The herdsboy in the Ten Oxherding symbolizes the practitioner of Dharma, and the ox represents the inherent spirituality that he/she tries to restore. The ten stages of the herding depict the corresponding phases in our soul-searching journey. Patriarchs of Chan/Zen Buddhism cast the ox as a symbol of our mind, and to reveal the inherent spirituality, or Buddha Nature, we must herd the ox by prying open the origin of the mind. The Ten Oxherding is a sequence that points to the proper way of practicing Chan/Zen Buddhism with implied instructions applicable to our daily life. Pay a visit to the Ling Jiou Mountain, where the mountain of spirituality and boulder stones with sacred stories come together. Here is our heart-felt welcome to everybody to visit the place for meeting their inner-ox by checking out the ten fabled boulder stones corresponding to the Chan/Zen story of the Ten Oxherding picture. Let your mind be ready for the reset button to experience a mind-settling journey that heals. Our first stop correlates to the Ox-searching phase that unfolds to tell of the story how it all started. With Brother A-Ken sharing the tale of the three stonemasons, we gaze into history by observing the LJM version of the Ashoka Pillar for a guidepost to lead us out of the wilderness with a dim illumination to uncover the original purity from within.

Pay a visit to the Ling Jiou Mountain, where the mountain of spirituality and boulder stones with sacred stories come together. Here is our heart-felt welcome to everybody to visit the place for meeting their inner-ox by checking out the ten fabled boulder stones corresponding to the Chan/Zen story of the Ten Oxherding picture. Let your mind be ready for the reset button to experience a mind-settling journey that heals. Our first stop correlates to the Ox-searching phase that unfolds to tell of the story how it all started. With Brother A-Ken sharing the tale of the three stonemasons, we gaze into history by observing the LJM version of the Ashoka Pillar for a guidepost to lead us out of the wilderness with a dim illumination to uncover the original purity from within.

(related article: Guided Tour of the Holy Mountain - The Ashoka Pillar)

► Download the digital calendar entitled Visit LJM for Meeting the Inner-Ox

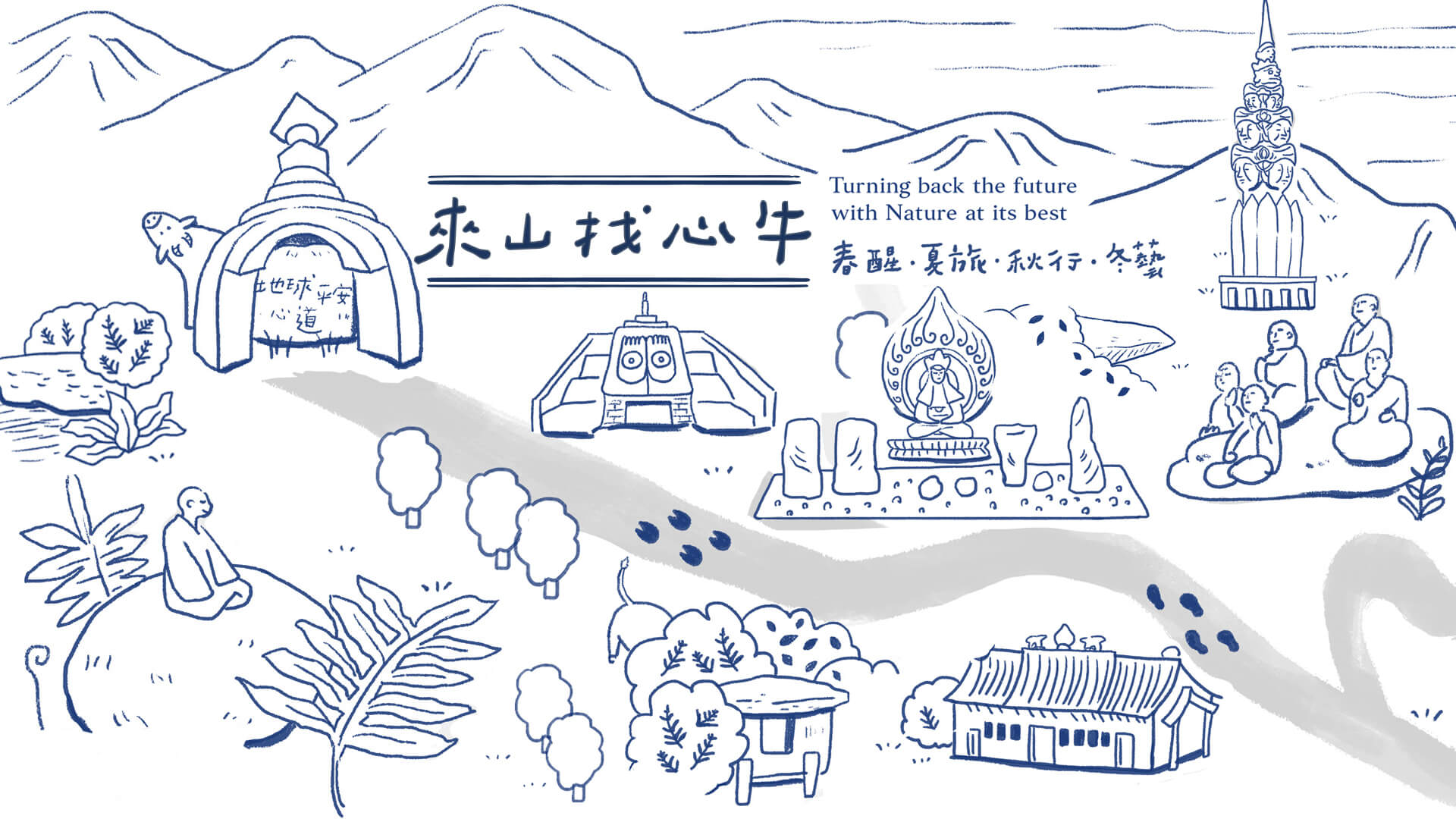

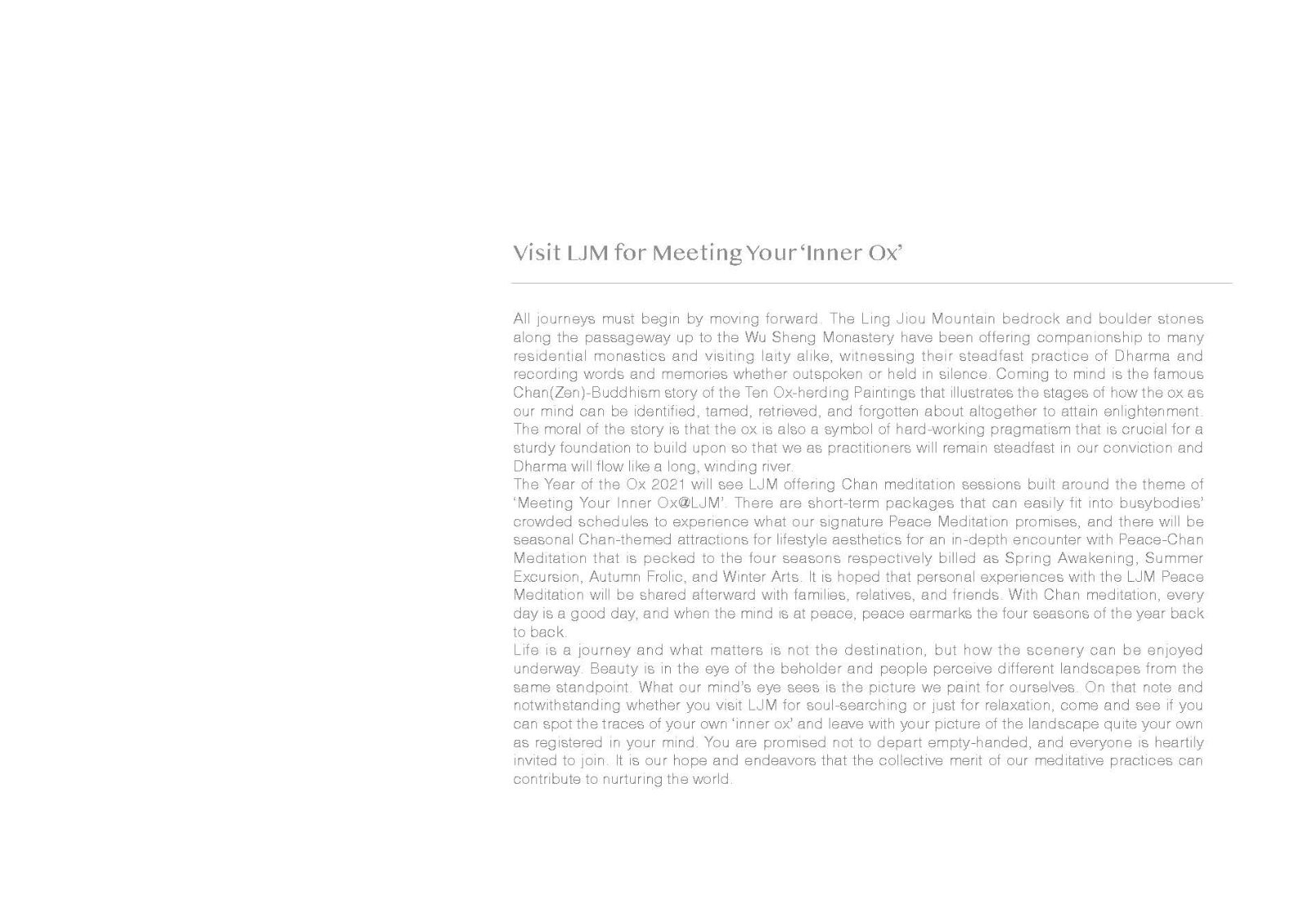

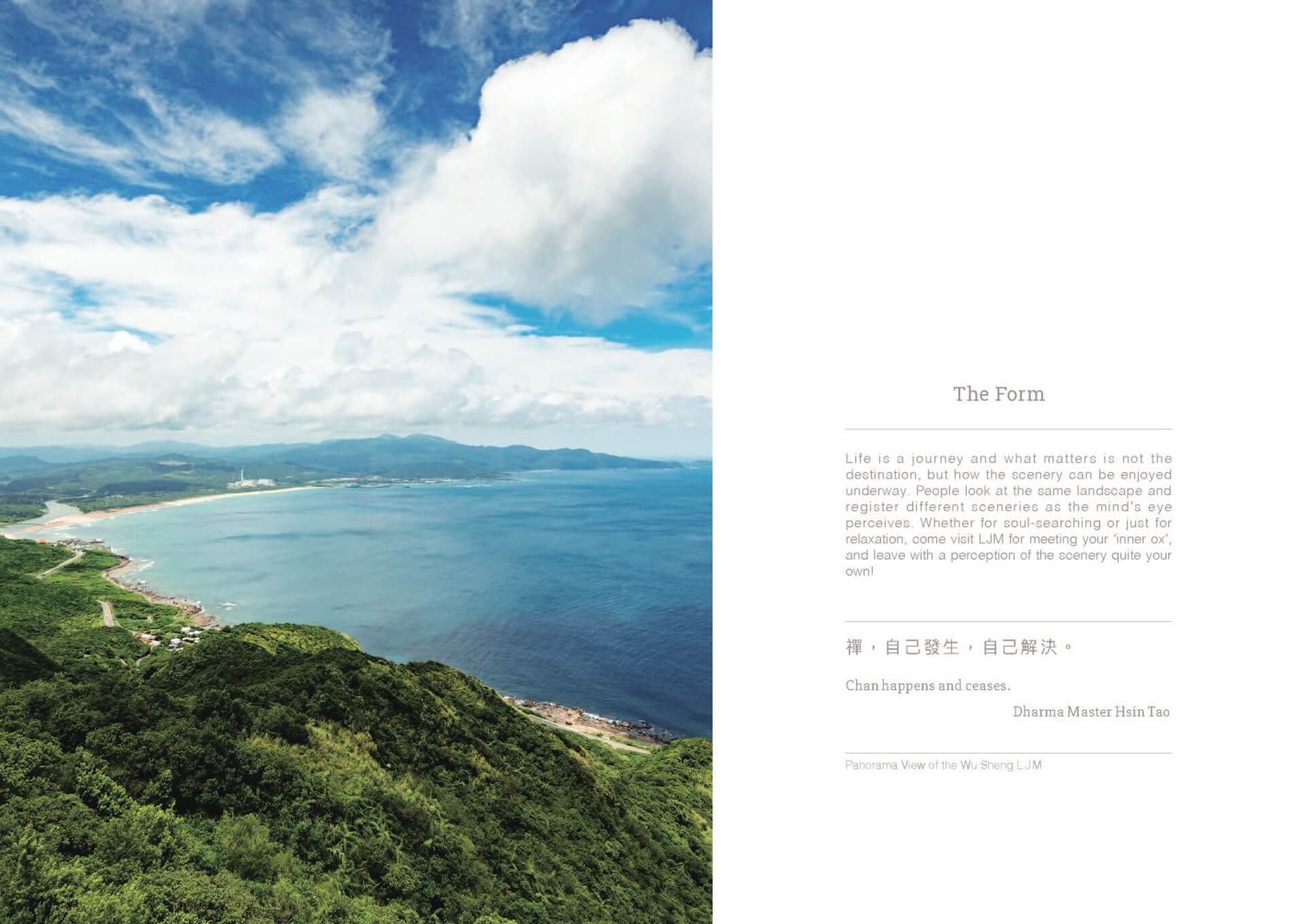

Meet your “Inner-Ox” at LJM

The digital calendar entitled Visit LJM for Meeting the Inner-Ox reflects our commitment to sustainability and respect for Nature in line with environmental friendliness while helping to outsmart limitations imposed by COVID-19 for viewers to enjoy scenic spots of the landscape surrounding the LJM Wusheng Monastery. Each picture of the calendar displays the beauty of tapestry made of natural elements like the woods and stones amidst mountain- and seascapes. A matching quote of the teaching of Dharma Master Hsin Tao keeps us company on our soul-searching journey. When the mind stays the course of Chan/Zen to remain free of clutter and contamination, your days are then always good and peace is yours to keep all year round. At the top of the new year, it is only fair that you go for blessings anew by signing up for a journey to the full content of the mind in the fashion of the Ten Oxherding.

Visit LJM for Meeting the Inner-Ox to Guard against COVID-19

All journeys must begin by moving forward. Since Master Hsin Tao founded the LJM Buddhist Society 38 years ago, boulder stones up in our mountain range have been constant companions to the residential masters in their practice. Rich with their own stories, the boulder stones are also witnesses to journeys of the mind of many LJM followers from all over. In the frequently quotedTen Oxherding Poems, Chan/Zen Master Guo An of the Sung Dynasty famously employed the metaphor of how a herdsman tamed an ox to suggest the stages of Chan/Zen practice and training to rediscover one's inherent Buddha Nature. As the Chinese pronunciation for expressions like “stone oxen” and “stone treading” are identical with “ten oxen” and “solid and hardworking”, ten famous boulder stones were selected as the building blocks for the annual theme to echo the historic Chan/Zen anecdotes, while highlighting our promotional tagline for meditation retreats.

"Every day is a good day in the presence of Chan/Zen; Peace is with you all year round when the mind is at peace." Safeguarding our mental immunity against COVID-19 can not be neglected before the pandemic is officially contained. The LJM has thus launched its travel-lite series pecked to the annual theme of the ten boulder stones for the Ten Oxherding anecdotes. Our signature offering - the popular LJM Peace Meditation - has thus taken up seasonal themes for 2021 that are Spring Awakening, Summer Excursion, Autumn Frolic, and Winter Arts respectively to help savor the beauty of Chan/Zen in life. One may furthermore expect to meet their“inner ox” at LJM with such meditation experience.

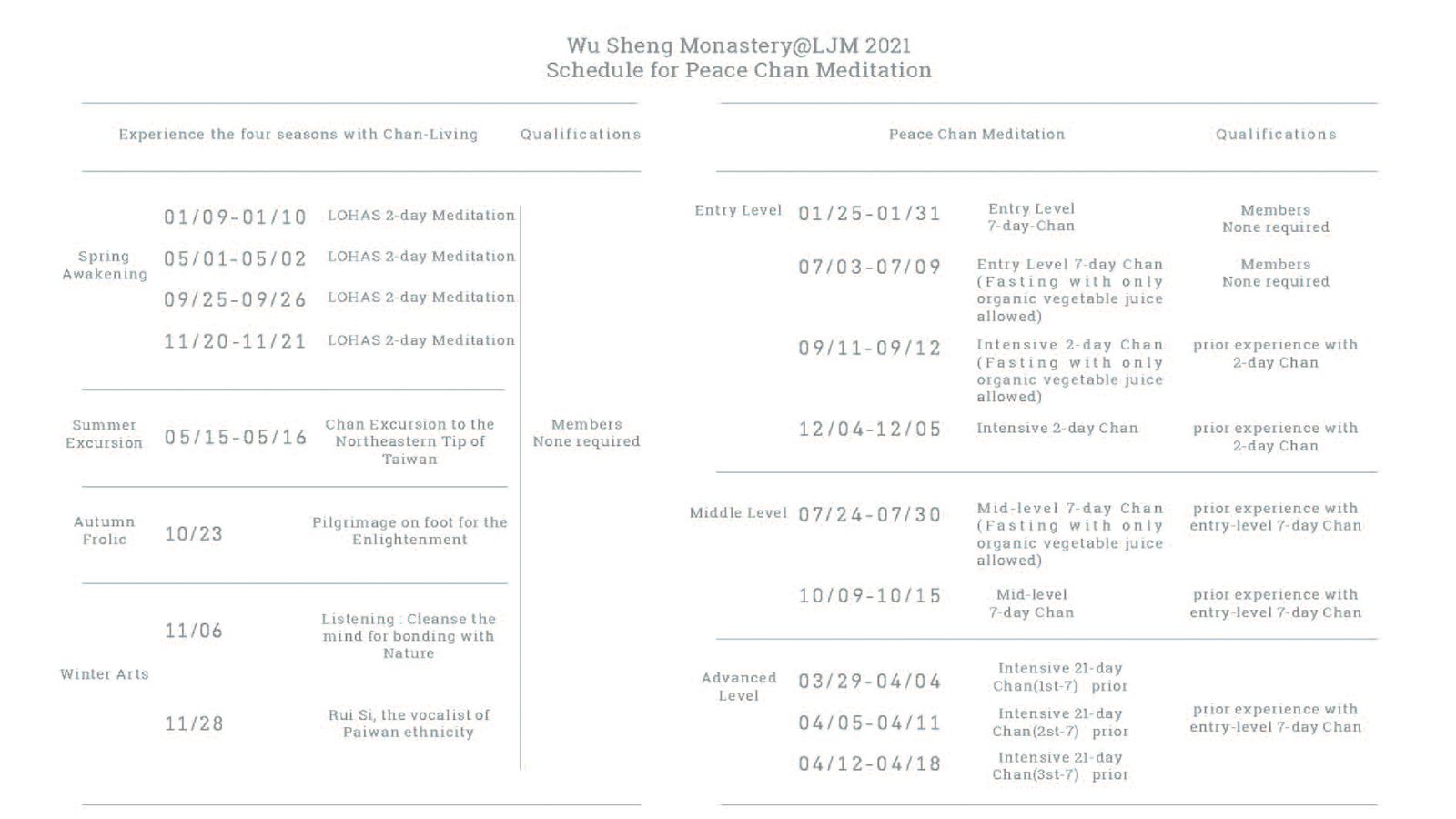

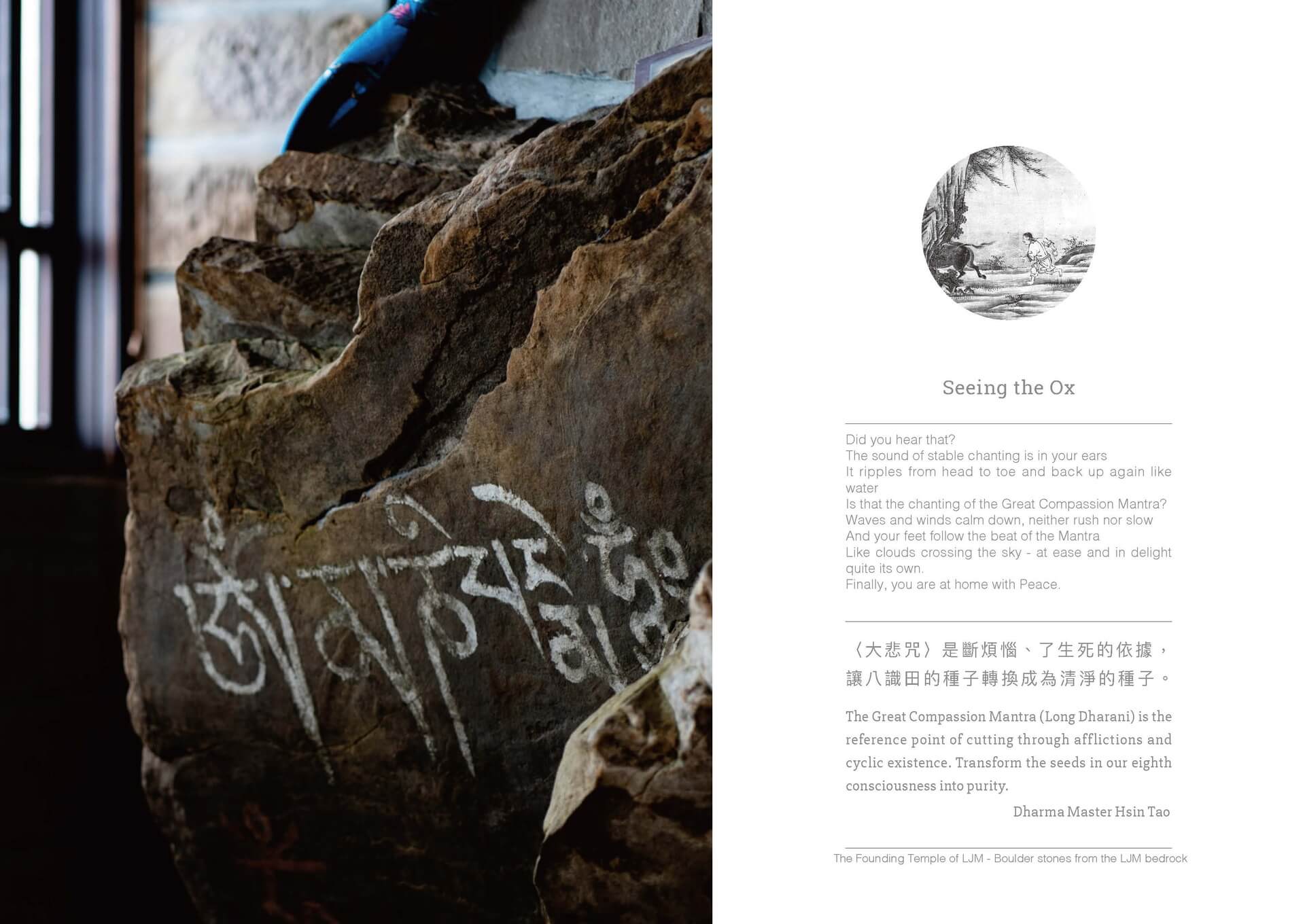

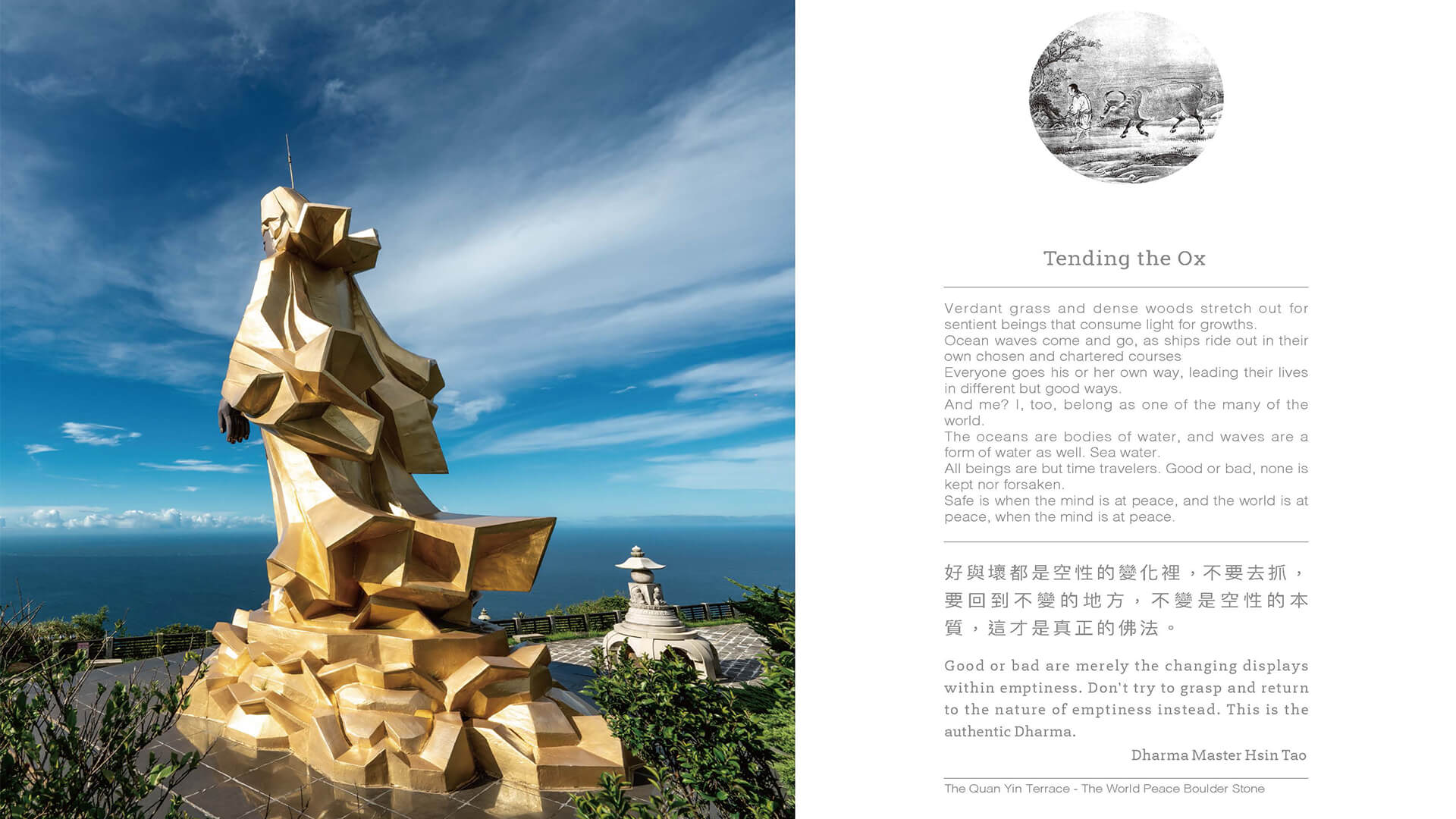

The Ten Oxherding is a series of ten drawings that depict ten scenes to symbolize the ten stages of Chan/Zen practice and they are entitled respectively as “Searching for the Ox”, “Seeing the Footprints”, “Seeing the Ox”, “Catching the Ox”, “Tending the Ox”, “Riding the Ox Back Home”, “Forgetting the Ox, the Oxherder Rests Alone”, “Both the Herder and the Ox Are Forgotten”, “Returning to the Buddha Nature” and “Returning to the Secular World with Helping Hands”. The ten matching boulder stones of Ling Jiou Mountain are as follows: the Ashoka Pillar, the stone sculpture in the shape of the feet of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra, the Founding Boulder Stone from LJM bedrocks, the Eagle-shaped hilltop rock, the World Peace Stone at the Guan Yin Terrace, the Four Heavenly Kings Stones, the Fa-Hwa Cave, the Stone of the Indigenous, the Balancing Stone at the Guan Yin Terrace, and the 500 Arhats.

Correlating to the “Searching for the Ox” phase in the case in point is the Ashoka Pillar upon the entrance of the LJM Upper Monastery. To observe the tall structure, you need to lift the head and look up, which is a motion people rarely do nowadays due to our modern-day lifestyle. In other words, in front of the Ashoka Pillar, we are reminded to examine our life and start searching for the inner-ox that lost its way in our fast-paced information era of a material world of consumerism. The resulting restlessness, frustration, and anxiety need to be handled with care and the LJM Peace Meditation makes a sensible choice for a good start by helping to calm down and gradually re-discover an inner strength to forge ahead in search of an innate clarity and purity.

Following that is the “Seeing the Footprints” stage that suggests a gradual appreciation over time of some of the basics to know if the mind is free of attachments. By the same token and by looking at the LJM stone sculpture in the shape of the feet of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra, we think back to what Dharma Master Hsin Tao means when he uses the phrase “non-arising nor ceasing” and it dawns on us that persistence over time pays out and we begin to make sense of the footprints that used to confuse us earlier.

The “Seeing the Ox” phase is equivalent to the first time when you catch a glimpse of your Buddha Nature. Put differently, Buddhism used to be a belief before, and truth after the said phase with the Buddha Nature revealed. In other words, you now know how to break away from the blocking of ignorance. The correlating LJM boulder stone is the bedrock at its Founding Hall, which bears witness to its history of 38 years and the responsibility of the future in the New Normal. While much remains yet to be seen for most people, the LJM bedrock testifies to its determination of staying true to its mission and commitment to its inheritance of Dharma teachings.

“Catching the Ox” refers to the stage where the appreciation of our Buddha Nature has been attained with much toil, yet deep troubles with attachment abound. The awakening led to realization and appreciation of the Buddha Nature that is without form or phenomena, but the opposite appears in the presence of inhabitancy. That compares to climbing out of the valley of troubles to reach the mountain top that is sometimes enshrouded in clouds of trouble. The correlating LJM stone is the Eagle-shaped hilltop rock formation that symbolizes the learning curve from “seeing the mountain as such” over “seeing the mountain as none” to “seeing the mountain as such still”.

“Tending the Ox” denotes the continued practice after the enlightenment with the notion that “to work is to practice” and that “life itself is our field of merit”. The clean-cut notion ought to be kept alerted and we ought to maintain the realization that any and all Dharma arises from the mind and our determination to stay steadfast to Dharma should never be swayed or otherwise influenced by the consciousness or any other subjects to maintain the mindfulness through all thick and thin, and to stay devoid of attachment as well, for the clarity of the thought and the purity of the mind to become one in presence. In other words, “Catching the Ox” renders the Ox and the herder as one, and “Tending the Ox” fuses the herder with time and space into the oneness of the presence of the moment. The corresponding imagery relates to the World Peace Stone at the Bodhisattva Tara Terrace of LJM to connect the dots linking LJM efforts for sustainability and ecology under the banner of “Loving the Earth” that include the Peace movement, beach cleaning and the “Great Compassion Mantra Retreat” that collectively transfer the merit back to Mother Earth.

With “Riding the Ox Back Home”, the herder gradually becomes homeward-bound toward the state of non-arising nor ceasing and the ox has been tamed to follow your will to the tee. Your mind becomes free and unconstrained by virtue of the solid practice of Dharma and its wisdom. Your peaceful state of mind is based on the result of your practice to NOT have any attachment - which can be likened to the Four Heavenly Kings stones (for stability) and the four pieces of deadwood (for stillness) there at the Yuan Tung Hall of the Upper Monastery that represent the eight Vajra-Spirits of the Diamond Sutra who safeguard Dharma for it to spread out in all ten directions. Continuing to deepen their studies of Buddhism in our Chan/Zen halls and subscribing to the notion that spirituality is the homestead, LJM followers practicing Peace meditation are literally herders riding their oxen home to regain the Buddha Nature for ultimate freedom.

And the drawing of “Forgetting the Ox, the Herder Rests Alone” suggests that once the ox is tamed, it ceases to exist. It goes to stress the learning that once the Buddha Nature is re-discovered, one has attained enlightenment to achieve a One-ness with their inner-ox. There is no longer any need for the footprints and they vanish. The correlating boulder stone of LJM is the Fa Hwa Cave, where Dharma Master Hsin Tao conducted his solitary retreat with fasting for over two years to go the ultimate lengths in examining his inner-ox down to the finest details. The hardship of early challenges to LJM only served to strengthen the determination of the Buddhist society that has developed to a global influencer forever dedicated to the teachings of Buddha.

“Both the Herder and the Ox Are Forgotten” describes the stage when speech, thought, and deed all cease to carry any significance. The oneness resulting from the fusion between the herder and the ox actually stems from the acute awareness based on the consciousness that depends on the five senses for perception and understanding of the world. Over time, both the ego-centric insistence and the Dharma-centric persistence become obsolete and you fully appreciate that everything in the world is interconnected. There are a number of works of stone of apparent indigenous origin in the mountains of LJM that remain untouched to stay in line with the respect of Dharma Master Hsin Tao for an interdependent symbiosis of universal diversification. The LJM Wusheng Monastery is thus a quasi hall of Nature, alive and full of Chan/Zen.

“Returning to the Buddha Nature” depicts the stage when the mind stays free of wanton desires and attachment regardless of the sound and form of any and all external phenomena, yet all Dharma keep out of the way of one another. With the enlightenment, omni-obstacles perceived before would turn into complete liberation everywhere for the so-called total freedom. The corresponding boulder stone at LJM is the Balancing Stone at the Guan Yin Terrace - a scenic spot fit for meditation to experience and realize whether the motions of the wind, the seawater, and the boats are external phenomena or internal perceptions.

"Returning to the Secular World with Helping Hands" is a drawing that depicts a Chan/Zen state of mind of entirely natural purity and child-like innocence. Once achieving enlightenment, you perceive things as they are, but at the same time, you also realize that everything is basically impermanent. You perceive the pseudo-haves of everything and also their ultimate existence of the middle path that the truth always lies between extremes. The correlating boulder stones are those entitled the “500 Arhats” who reside in the four famous Buddhist mountains to embody the notion that Dharma is among us and thus available to help us reach enlightenment. On that note, it may be worthy of your attention to learn about Dharma Master Hsin Tao and the popular LJM Peace meditation are reason enough for you to join us for a leading Dharma approach to the tradition of Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara to emulate in the vow of great compassion as part and parcel of the LJM initiative of “Loving the Earth” and “Loving Peace” for sustainability and ecology of a brave new world.

► Download our digital calendar entitled Visit LJM for Meeting your Inner-Ox

Seeing Thy Inner-Ox - But Not Before The Creek Stone of The Bhikkhu

It is said that many people learn about, or even practice, Buddhism nowadays. But few really own the right knowledge and right insight of it. What, then, is the ‘knowing insight’? It is about recognition and comprehension and it refers to that of Buddha Dharma and secular Dharma. Once that recognition is achieved, the ‘knowing insight’arises. Thus accordingly, Buddha Dharma facilitates the acquisition of the Knowing Insight. It helps guide the practice of Buddhism like the GPS-triangulation for navigation in traffic or out in the ocean. Paranoia steps in when practicing Buddhism without the Knowing Insight.

Suppose you are told that Buddha is the heart and mind, and none without. Or even the claim that there is no Buddha at all. You would probably laugh it off and say, ‘I know all about it, no matter whichever way you tell it’The recognition affords the realization that the Original Self is indeed non-form and non-phenomena, and there is no wondering any more whether there is life after death, or if past lives ever exist. At the end of the day, past and future devoid of time are reduced to cognitive elements for instant recurrence in our consciousness. None is lost in the presence of the moment when the pure Original Self remains a conscious perception. That is bodhicitta, present at all times.

But, suppose we have yet to find out about the Original Self, meaning we have not yet seen our Inner-Oxen, what then? You are best advised to keep a crystal clear and clean heart without wanton desires nor attachments. Steer clear of all sentimental reactions ensuing from a hardening or comforting experience. Remain clearly conscious without getting emotional and you are free of fears and worries once you become so conditioned. Such is the state of unconstrained ease and being in its own element.

Before this stage, Dharma is a matter of faith to some people, who are willing to study and believe Buddhism that sounds plausible, while consequent practice in proper ways (such as via meditation or controlled breathing) that eventually afford the Knowing Insight to allow glimpses of the Inner-Ox. Thereupon you enter the phase of ‘Seeing Thy Inner-Ox’and you get a peek at your own fundamental awareness, i.e. the consciousness, and Dharma transcends mere faith to become the truth. But you are by far not relieved yet, as the Inner-Ox has just been tamed recently and thus not quite under control. The newly acquainted Original Self, likewise, is still unstable in your perception and consequently easy to get lost. Hence we see the herdsboy with the harness for control.

When we enter the phase of ‘Seeing Thy Inner-Ox’, life ought to be ushered into purity as well. Precepts provide the best possible guidance at this time that caution us when we get too close to the edge of a clift. The Creek Stone fable illustrates how the Inner-Ox inflicted self-confinement and how karma can be reversed by the power of vows, which also points to the way out from the scenario that the Inner-Ox gallops in all directions in vain to break away from its innate limitations. The empowering vows ultimately triumphs over karma.

The above can be likened to the journey how the Ling Jiou Mountain founding abbot, Dharma Master Hsin Tao, started from scratch to humbly yet securely bring the LJM Buddhist Society to where it stands now, evidenced by the boulder stones for the foundation of the LJM monasteries, as well as echoed by those rock formations adorning the LJM premises. Over the span of thirty-plus years, from the first-ever interfaith Museum of World Religions to the making of the future University for Life & Peace, the importance of world peace has been eloquently demonstrated for all to see in Master Hsin Tao’s relentless efforts.

His now popular quote - The World is at Peace when the Heart is at Peace - delivers solid evidence and proof that the power of vows surpass that of karma.

.JPG)